JPD Has A Pattern Or Practice Of Using Unreasonable Force

We find reasonable cause to believe that JPD engages in a pattern or practice of unreasonable force[1] in violation of the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and Illinois law. Our findings are not limited to any one type of force, tactic, or context. However, over the course of our investigation, we observed several trends including:

- a failure to de-escalate and a tendency to unnecessarily escalate situations

- unlawful use of retaliatory force

- unlawful use of tasers, head strikes, and other bodily force

- concerns about gun pointing practices

- excessive force against teenagers and people with behavioral health disabilities

- a failure to intervene when unreasonable force is being used by another officer

Factors that contribute to this pattern include:

- supervisory deficiencies at every level of JPD’s review of force

- deficiencies in JPD’s use of force policies and training

- a department culture that overlooks policy violations and seeks to justify all force used

Officers often confront dangerous situations that put their own safety and the safety of others at risk. They face split-second decisions and are required to react quickly to fast-changing situations. Inevitably, mistakes and misconduct will occur and when they do, meaningful supervision, support, and accountability are vital. JPD has consistently failed on these fronts. Although our office identified numerous unreasonable uses of force between 2017 and 2022, our review of JPD’s supervisory and force panel review documents, as well as JPD’s Internal Affairs files, revealed that these accountability entities rarely recognized unreasonable use of force.[2] JPD’s repeated failure to identify and address unreasonable force is not an aberration—it is a hallmark of its supervisory culture. The Department’s inability to police itself sends the message from the top down that nearly any force can be justified and that there are no consequences for using unreasonable force.

JPD’s repeated failure to identify and address unreasonable force is not an aberration—it is a hallmark of its supervisory culture.

Legal Standards

Police may use a reasonable amount of force for any legitimate law enforcement purpose, including making lawful arrests or defending themselves or others against physical harm.[3] But both the U.S. Constitution and state law limit when and how much force an officer can use. Under the Fourth Amendment, force must be “objectively reasonable” based on the “totality of the circumstances” as perceived by a “reasonable officer” at the time.[4] To be objectively reasonable, force must be proportional to the threat posed.[5] Illinois law echoes the constitutional standard and adds that the authority to use force “is a serious responsibility that shall be exercised judiciously and with respect for human rights and dignity and for the sanctity of every human life.”[6]

Although hindsight is important for improving tactics, policies, and trainings, the question of whether force was lawful is limited to the perspective of a reasonable officer at the time force was used.[7] To determine whether force was objectively reasonable and proportional, courts consider several factors, such as:

- the severity of the suspected crime

- the threat reasonably perceived by the officer(s)[8]

- whether the person was actively resisting arrest or was attempting to flee

- the relationship between the need for force and the amount of force used

- the severity of injury (though force may be excessive without injury)

- any efforts made by the police to temper or limit the amount of force used[9]

An officer’s intent is not a factor in assessing the reasonableness of force used.[10] This means that a well-intentioned officer might have acted unlawfully, and an officer with bad intentions might still have used lawful force. In addition, “[e]ven when officers’ goals are eminently reasonable, there are definite limits to the force officers may use to prod arrestees into obeying commands.”[11] For example, “substantial escalation of force in response to passive non-compliance” with an officer’s orders is unconstitutional.[12] Each use of force must be “evaluated carefully and thoroughly.”[13] If an officer strikes someone three times, the first might be justified, while the second or third may not as circumstances evolve.[14]

Overview of JPD’s Policies and Procedures for Non-Deadly Force

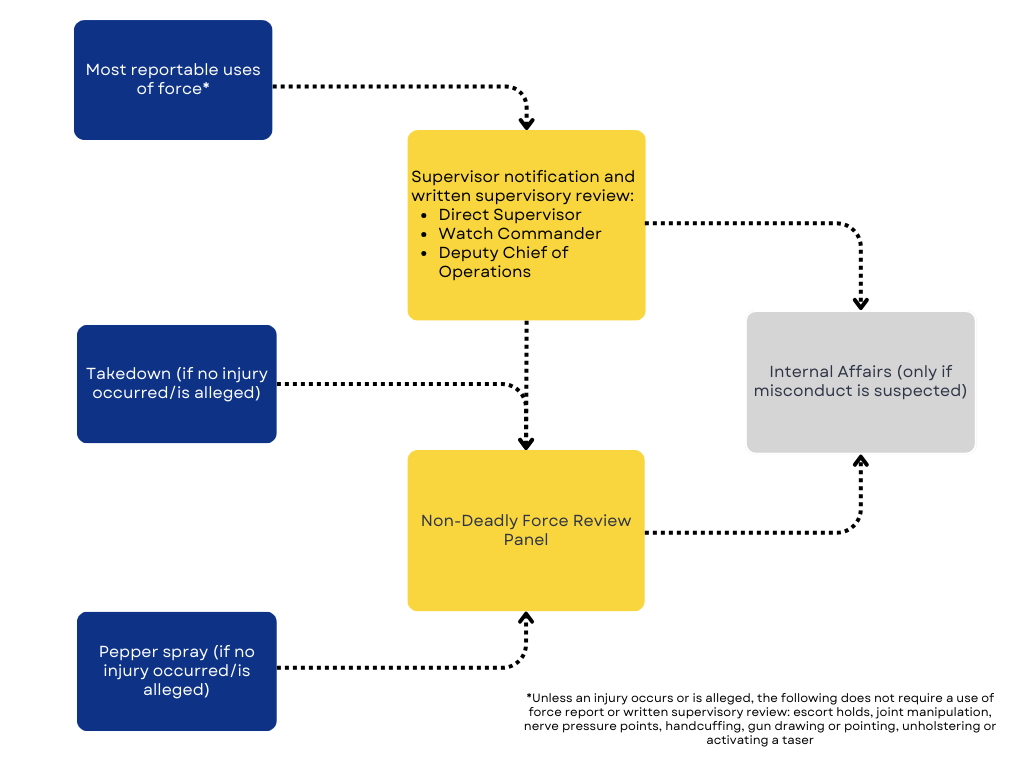

JPD policy permits non-deadly force only when necessary to protect from physical harm, to restrain or subdue a resistant individual, or to bring an unlawful situation safely and effectively under control. Officers must complete a written report for most uses of force. Exceptions include lower-level force (such as escort holds, joint manipulations, or touch pressure) if the force did not result in an injury or alleged injury. Officers are not required to complete a report when they draw or point their gun or when they activate their tasers.[15] Most reportable force goes through two layers of review: (1) the supervisory chain of review (on-duty sergeant, watch commander, and deputy chief of operations) and (2) a force review panel.[16]

Broken bridge on Des Plaines River

Methodology

In evaluating the reasonableness of JPD’s uses of force, we considered the perspective of a reasonable officer at the time the force was used, without considering information known only in hindsight. Our analysis of JPD’s use of force relied on a range of evidence, including:

- Use of Force Documents. We reviewed a random sample of JPD’s more than 1,000 non-deadly reported uses of force from 2017 through 2022 stratified by use of force type (e.g., empty hand strikes, takedowns, etc.)[17] and every deadly use of force from 2017 through 2023. Our review included arrest reports, officer narratives, video (including from squad car cameras, body-worn cameras, or taser cameras),[18] photographs, force reports, supervisory review reports, and force review panel recommendations.

- Internal Affairs Documents. We reviewed Internal Affairs files from 2017 through 2022 stratified by use of force that involved use of force complaints. This review included the force documents listed above as well as shift-level counseling files, complaints, officer and complainant interviews, investigation reports, and records of any discipline or remedial training.

- Data. We reviewed JPD’s annual use of force reports from 2017 through 2022. Our data experts also analyzed force data from JPD’s databases.

- Policies and Training. We reviewed JPD’s force policies, training materials, and observed trainings in person and via video recordings.

- Observations. We observed non-deadly and deadly force review panel meetings, shadowed 911 Communications Center workers, and went on ride-alongs with officers.

- Officer Input. We conducted numerous meetings, focus groups, and one-on-one interviews with JPD command staff, supervisors, line officers, and unions.

- Community Input. We interviewed and held focus groups with community members and community organizations. We also reviewed all emails and voice messages we received from community members about this investigation.

Together, these sources of evidence establish reasonable cause to believe that JPD officers engage in a pattern or practice of using unreasonable force. We also saw indicators of reportable force during this period without corresponding force reports. In light of evidence of missing force reports and cases where officer reports conflicted with video evidence, this pattern may be broader than what our findings document.

Findings

We find that JPD has a pattern or practice of using unreasonable force that is not limited to any single weapon, tactic, or context. Within this overarching pattern, several trends emerged. First, JPD’s uses of force demonstrate a failure to de-escalate—and a tendency to actively escalate—encounters, leading to avoidable or excessive uses of force. From command staff down, JPD embraces the outdated mindset that using force early avoids the need for more force later. We noted repeated instances where JPD’s tendency to “come in hot” confused or antagonized the persons involved, leading to disproportionate use of force.

From command staff down, JPD embraces the outdated mindset that using force early avoids the need for more force later.

JPD’s use of excessive force spans a variety of force types, but we have particular concerns about tasers and head strikes, including a tendency to use them repeatedly, without a commensurate threat. These concerns often overlapped with unnecessary escalation or retaliatory force and included instances of unreasonable force against teenagers and people with behavioral health disabilities.[19] Officers rarely intervene when other officers use force unreasonably and supervisors rarely identify, much less correct, this behavior.

This pattern is harmful to the very community that JPD is sworn to protect. It makes people less likely to cooperate or view police as a legitimate authority. JPD’s use of escalating tactics and unreasonable force has unnecessarily traumatized community members and amplified distrust of police, particularly among Black and Latino members of the community.[20]

We describe various force incidents that illustrate JPD’s pattern of unlawful use of force in this Report. These examples are only a subset of the unlawful uses of force that we identified. A single force incident might include both positive and negative actions by officers, and our purpose in pointing out patterns of unlawful or problematic behavior is not to discredit the positive but, rather, to highlight issues that have continued unchecked across multiple administrations.

JPD’s response to a gathering of young people celebrating Mexican Independence Day in 2023 is one of many problematic examples. The incident began when JPD responded to concerns about cars doing burnouts in a Joliet Park District parking lot.[21] A sergeant immediately set a combative tone by speeding into a group of peaceful pedestrians, opening his door with the engine still running, and abruptly accelerating several more feet towards people. This dangerous maneuver rapidly deteriorated the situation. People began complaining and mocking the sergeant, but video shows that they were not physically threatening him. Rather than attempt to de-escalate, the sergeant called for tow trucks and instructed an officer to “Block this piece of sh*t [car] in.”

Upset at almost being hit, a young man stuck his middle finger through the open squad car window. The sergeant shoved the door open further, prompting people to shout that the officer hit the man with the car door.[22] When a person said they would report the sergeant’s behavior, the sergeant responded, “You’re going to tell on me? That’s cute.”

The sergeant later spotted the same man walking slowly away and chased him with a taser. When the man got away, the sergeant turned to threaten random bystanders with the taser, including one man who had his hands up. The sergeant’s indiscriminate and retaliatory threats of force against people who were not suspected of any offense further escalated the situation. An officer stepped in at that point, defusing the tone and telling everyone to back up.

Meanwhile, another sergeant drove up, pulled out pepper spray,[23] and began yelling, “Get the f*** out of here!” He shoved a young man several times and walked him backwards by the shirt while ordering him to leave. Nearby, another young man approached and motioned at the sergeant, saying, “Don’t be putting hands on my boy!” The sergeant shoved him back by the throat and then immediately pepper sprayed him in the eyes, while screaming “LEAVE, GET THE F*** OUT OF HERE!”

While some force may have been justified in stopping the young man from approaching, it was unreasonable to immediately pepper spray him in the eyes when he was not posing a threat. It also violated JPD policy, which requires a verbal warning and opportunity to comply, and raises state law concerns, which prohibits force used as punishment and using pepper spray for crowd control without giving “sufficient time and space to allow compliance.”[24]

A minute later, the sergeant returned to the young man he pepper sprayed, who was pouring water in his eyes. The sergeant repeatedly screamed at him to drive away, despite his friends explaining he was in no condition to drive. The sergeant also threatened others with the pepper spray, focusing on bystanders filming with cell phones, raising First Amendment concerns.[25]

Many problems identified above could have been minimized or avoided if these two sergeants had employed de-escalation techniques. Notably, some officers did effectively use de-escalation. One repeatedly used tactics to lower the temperature of both the crowd and officers. This shows how professional behavior by some officers can be severely undermined by overly aggressive tactics of other officers. It also underscores problems that can take root when supervisors themselves model bad behavior. Regardless of policy or formal training, front-line supervisors’ actions speak louder than words.

The supervisory chain of review and force review panel found all force associated with the events on Mexican Independence Day to be reasonable and within policy, and there is no record of any shift-level counseling, remedial training or corrective action.[26] And no one identified any of the several inconsistencies in the force reports, including officer justifications contradicted by video. For example, officers arrested the man who gave the sergeant the middle finger for obstructing and aggravated battery against an officer. The arresting officer stated that he saw the man “running towards me. I grabbed [him] but he continued to pull away. [He] grabbed onto my vest, and the left side of my torso as I attempted to pin him against a vehicle.” However, video shows that the man was slowly walking in the arresting officer’s direction when the officer rushed forward, slammed him against a pickup truck, and arrested him.

An anonymous community member later submitted a complaint to JPD, which stated:

Shame on that officer [who threatened people with a taser]. No de-escalation tactics were used, this [was] conduct unbecoming of an officer. He clearly wanted confrontation to the point of chasing someone down and repeatedly threatening them with force for what crime? You create the divide.

JPD’s Internal Affairs concluded that because probable cause existed for the arrest, the complaint would not be investigated. Regardless of whether there was probable cause for arrest, a host of problematic police behavior exacerbated the incident, and the lack of meaningful review harms the public and the Department.

The fact that neither sergeant received corrective action is particularly concerning, given that sergeants are responsible for reviewing other officers’ uses of force. The two sergeants’ impunity reinforced officer and public perceptions that inappropriate behavior is acceptable. Referring to this incident, an officer told us that sergeants can do whatever they want because no one wants to write up sergeants—no one wants to be the “bad guy.”

This incident is only one of many that we identified as involving unreasonable force with no accountability. The following sections detail this pattern and discuss contributing factors.

JPD officers often fail to use de-escalation and procedural justice strategies, resulting in avoidable and unreasonable force

JPD’s unreasonable uses of force often stem from a recurring failure to de-escalate—and a practice of actively escalating—encounters. This escalation includes a tendency to “come in hot”—shout commands, threaten to use force disproportionate to the risk, and use force if the person does not comply quickly, even where the person does not reasonably pose a safety threat.

As first responders, police handle potentially volatile situations. De-escalation tactics provide officers with tools to try to resolve interactions “through means other than force and to minimize the extent and severity of force when it is deemed necessary.”[27] These means may include speaking calmly, non-verbal communication, tactical positioning to increase time and distance, and critical thinking skills to pivot with changing dynamics.[28] De-escalation strategies are closely tied to the principles of procedural justice, which include giving people a voice; engaging in unbiased, transparent decision-making; treating people with dignity and respect; and conveying trust-worthy motives and concerns.[29] De-escalation and procedural justice strategies can increase the likelihood that encounters resolve in a less harmful way for both police and the public. While de-escalation is not always feasible, it has been shown to help minimize uses of force and reduce officer and community injuries.[30]

De-escalation and procedural justice strategies can increase the likelihood that encounters resolve in a less harmful way for both police and the public.

Both state law and JPD policy recognize the importance of de-escalation. Since 2023, Illinois law has required de-escalation training “to prevent or reduce the need for force whenever safe and feasible,”[31] and JPD policy directs officers to use de-escalation when possible. JPD’s code of ethics also states that “[f]orce should be used only with the greatest restraint, and only after discussion, negotiation and persuasion have been found to be inappropriate or ineffective.”

JPD’s de-escalation trainings reference some best practices, such as using positioning to slow things down, body language awareness, and using a calm demeanor. Trainings also encourage officers to give people the opportunity to voice their perspective, summarize back to people what they said, and project sincerity and courtesy. In practice, we observed some officers using these techniques effectively to peacefully resolve incidents. We also saw some officers go above and beyond to establish rapport and care for subjects in a dignified, respectful manner. One officer shared that “if you tell the truth to a suspect about why you are making contact, or why [you are] arresting them, then often force can be avoided. They are humans just like we are.”

Unfortunately, these positive examples are undermined by contradictory messaging and tactics that go unchecked. In many incidents that we reviewed, officers used an “ask, tell, make” approach, which aims to gain compliance through a quick escalation in demands rather than two-way communication.[32] JPD’s training and supervisors tend to frame de-escalation as a precursor to using defensible force. For example, trainings framed de-escalation in terms of “mak[ing] the attempt” to de-escalate for accountability purposes, rather than as widely applicable tools to reduce the need for force, decrease the likelihood of officer and community member injury, and build public trust. JPD trainings and supervisors also teach that using low-level force early can de-escalate by avoiding the need for more force later. As one lieutenant emphasized, using force early can “avoid a fight.” This “escalate early to de-escalate” approach is ingrained in practice and reinforced by JPD’s supervision and accountability systems.

JPD’s outdated approach does not align with best practices and instead encourages unnecessary escalation. In some incidents, unnecessary escalation led to unreasonable force against persons suspected of minor, non-violent offenses, including where the person did not pose an imminent threat. These offenses include, for example, minor traffic violations (such as a broken taillight, failure to use a turn signal, or failure to fully stop at a stop sign), trespassing, and shoplifting.

JPD’s outdated approach does not align with best practices and instead encourages unnecessary escalation.

One high-profile 2018 incident that escalated from a failure to fully stop at a stop sign illustrates a number of these concerns.[33] Squad car video shows that during the stop, the Black male driver and the Black female passenger felt they were being racially profiled. The officer did not explain the reason for the stop and ignored their questions. Instead, the officer repeatedly told the driver to roll the window further down and step out. The driver accused the officers of being racist. In response, the officer threatened to break the window if he did not exit the car.

Less than five minutes after the stop, and shortly after two backup cars arrived, the officer smashed the driver’s window with a baton. The officer then pulled the driver through the door and took him to the ground. Despite the man being immobilized on the ground with an officer controlling his legs, an officer struck his legs with a baton several times, causing him to move to avoid the pain and compromising the previously secure positioning. The leg strikes were not justified or proportional to any reasonably perceived threat. At that point, the driver was already secured and not resisting, there was no indication that he was a violent threat, and the underlying offenses of failing to fully stop at a stop sign and refusing to exit were low-level and non-violent. The driver had been argumentative and uncooperative, but the situation was contained and the occupants were not posing any threat justifying a violent extraction that increased risks to everyone involved.

Meanwhile, an officer tried to smash the passenger window with a baton (without apparent justification) before opening the door, pulling a 16-year-old Black male from the back seat, taking him down, and handcuffing him. From the video, there did not appear to be a justification for the takedown, and the teen was later cited for a curfew violation. An officer then pulled the crying front seat passenger out, walked her towards where the driver was arrested, and took her to the ground. The officer’s reported justification for using force—that the passenger tried to run towards the driver being arrested—is contradicted by video.

After finding no contraband, an officer exclaimed, “Are you f***ing kidding me?! All this for nothing!” Neither the supervisory review nor the force review panel identified any concerns, and no one flagged the inconsistencies between the officer reports and the squad car video.[34] Only one officer was disciplined; the officer who conducted the stop received a written reprimand for failing to give the reason for the stop. Internal Affairs did not examine the force or tactics used.[35]

In a 2019 example of a failure to de-escalate, officers saw a car with tinted windows driving slowly without lights around 1 a.m. When the car stopped at a red light, the officers activated their lights. As they exited their squad car, the light turned green and the car slowly crossed the street, pulling over just past the intersection. After parking, the driver, a Black man, obeyed commands to turn off the car, roll down his window, drop his keys outside, and keep his hands outside.

Despite no immediate threat, four officers approached, one with his gun pointed. The officers ordered the man out of the car; he became indignant and refused, insisting that he had his license, registration, and insurance. Rather than try to resolve the low-level, non-violent situation peacefully, officers threatened the man with a canine, and—just over a minute after first ordering him to exit—pulled him out of the car while another officer tased him in the back. Officers arrested him, charged him with resisting arrest, issued a citation for improper lighting, and towed his car.

JPD's failures to effectively de-escalate have been repeatedly flagged by community members.

The taser use was unreasonable.[36] Although the man was agitated and refused to exit the car, he was suspected of only a minor traffic infraction, had made no verbal or physical threats, and there was no indication of a weapon. He had turned off the car, dropped his keys outside, complied with orders to roll down windows, kept his hands outside, and was outnumbered eight to one with a canine present. At the time he was tased, he did not pose “even a potential threat to the officers’ or others’ safety, much less an ‘immediate threat.’”[37] There is no record of any supervisory concerns, and JPD’s force review panel had no recommendation.

JPD’s failures to effectively de-escalate have been repeatedly flagged by community members. As one community member shared, “JPD is very impersonal and they just try to intimidate you. When talking they often have their hands on their guns. I’ve seen them do it around kids and old people.” This feedback reflects a prevailing sense among segments of Joliet’s population that police are to be feared rather than trusted—a dynamic that we observed in many incidents we reviewed. For example, fear and distrust played a role in how people—particularly Black and Latino community members—acted when they were pulled over by JPD officers. In these and other encounters, officers dismissed or provoked people’s fear of police and unnecessarily escalated encounters.

JPD uses excessive force in retaliation for conduct its officers dislike

As a part of its unconstitutional pattern or practice of excessive force, we observed JPD using force in retaliation or punishment for conduct and speech that officers dislike.

Whether force was lawful does not depend on an officer’s subjective intent.[38] As it relates to punitive force, the “objective reasonableness” standard considers when force that may have been reasonable at one point in an encounter became unreasonable at the time it was applied.[39] The Fourth Amendment also prohibits an officer from using force as punishment for a failure to obey orders or passive resistance.[40] In 2021, Illinois law adopted the prohibition against punitive and retaliatory force, and JPD added the prohibition to its force policy.[41] However, the policy does not define punitive or retaliatory force, and we are unaware of any formal JPD training on the meaning and avoidance of punitive and retaliatory force.[42]

In some incidents we reviewed, JPD used force when it was no longer necessary to obtain a lawful objective, adding to concerns that the force served a different, retaliatory purpose. For example, in a 2020 incident, JPD officers used lawful force to effect an arrest of a person who had shown contempt toward the police at the outset of the encounter. However, after the person was subdued and no longer a threat, the officers’ continued use of force was unlawful.[43]

We also observed JPD officers appearing to use punitive force after escalating encounters and goading individuals. For example, during a 2022 traffic stop for a missing front license plate, three officers approached the car and asked the Black male driver and Hispanic male passenger to step out because the officers smelled cannabis. Officers helped the visibly intoxicated passenger exit the car and sat him on the curb. While a JPD canine conducted an open-air sniff (which alerted to the presence of narcotics), the passenger became verbally confrontational. He was belligerent and antagonizing, but the officers remained composed and largely ignored him. Approximately 15 minutes into the encounter, the passenger got up and stood near the driver at the hood of a squad car. Most officers continued to ignore the man, but one responded and escalated the situation by taunting the passenger to “step up” and “stop being all talk.” The passenger approached the officer, stating he would “punk [the officer’s] ass.” The officer told him to step back and appeared to push him back toward a squad car. The passenger stumbled with both hands behind him, and the officer shoved the man in the chest and told him to stay there. Two officers 15 feet away began to slowly walk towards them but did not attempt to intervene. The man stumbled in the direction of the officer, pointed at the officer’s face, and said not to touch him. The officer immediately punched him in the face, knocking him to the ground. Officers arrested the man and sought aggravated assault charges.

Will County Courthouse on Jefferson Street

The face punch was excessive and the result of the officer taunting the antagonistic man. The officer reported that he “feared [the man] may use his hand to strike” him when the man “pointed his right hand with two fingers extended inches from the [the officer’s] face.” However, the actions of the other officers on the scene reflected a lack of concern about a physical threat, as the passenger was much smaller than the officer and was having trouble standing. When the officer started to goad the passenger, a second officer nearby walked away to privately confer with a third officer—an action the officer would not have taken if he had any concerns about the man posing a threat. The officer’s force appears rooted in frustration and in retaliation for the passenger’s verbal taunts rather than for protection. Officers are expected to exercise a high degree of restraint and should not be provoked into misconduct by profanity-laden speech.[44] Neither the reviewing supervisor nor the force review panel identified any concerns. Rather, the supervisor stated that the officer “showed great restraint in dealing with the suspect for several minutes, until the suspect continued to come at him, placing [the officer] in fear of a Battery.” The supervisor’s failure to address the officer’s behavior, including daring an intoxicated subject to assault him, is tacit approval of unprofessional behavior and unlawful force.

JPD officers also use force against people who have fled, in an apparent attempt to punish them for their flight. Notably, officers have used force after the fleeing person ends their flight and is coming into compliance with the officers’ commands—and after a threat or other lawful basis for the use of force has dissipated. A 2019 incident following a call for service about a man checking car door handles in a parking lot exemplifies this pattern. There, squad car video shows the tail end of a foot pursuit that ended when the person fleeing fell to the ground. The pursuing officer then stands over the man, a White male, who was lying prone on the ground, and slaps him in the face. The officer reported that he slapped the man “in an attempt to stun him” because he was trying to get on his feet. But the video contradicts this: there was no sign that the man was still a flight risk (or posed a threat) when the officer slapped him, suggesting that the officer sought to punish the man for the pursuit. Another officer driving to the scene was recorded on squad car video announcing over the radio that he was going to “kick the sh*t out of this dude;” although this officer did not end up using force, his announcement indicated an eagerness and conveyed approval of the use of punitive force. The supervisory chain of review found the force to be reasonable, but the force review panel referred the incident to the Deputy Chief of Administration, who submitted a complaint to Internal Affairs. Internal Affairs administratively closed the complaint and referred the matter to the officer’s supervisor for shift-level counseling. Internal Affairs also recommended that the officer attend remedial training for report writing and use of force tactics, which the officer received seven months later.

JPD uses unreasonable and disproportionate force across various force types

JPD’s overarching pattern of using unreasonable force encompasses various types of force, including tasers, head strikes, and other bodily force. We also have concerns with JPD’s policies and practices around pointing firearms. Each of these types of force are part of the overall pattern of unlawful force. We discuss below several types of force that we found particularly concerning.

Tasers[45]

Taser use is part of JPD’s pattern of unlawful force. Tasers can be an effective force option when used appropriately. Tasers exert a significant amount of force, however, and require adequate justification. “The impact is as powerful as it is swift. The electrical impulse instantly overrides the victim’s central nervous system, paralyzing the muscles throughout the body, rendering the target limp and helpless. The tasered person also experiences an excruciating pain that radiates throughout the body.”[46] Tasers are JPD’s second most frequently reported type of force.[47]

JPD policy specifies when tasers can be used, including if a person poses a risk of harm to themselves, is actively aggressive or actively resists, or flees where there has been a severe crime, an immediate threat, or a history of violent behavior. But the policy is incomplete. It does not define concepts such as “active aggression,” “active resistance,” “passive subject,” “minor resistance,” or “resistance that is not hazardous,” all of which are critical to determining whether taser use is justified. The policy also does not clarify that each deployment must be separately justified.[48] This is especially concerning as the policy does not restrict prolonged or repeated taser use, which may pose greater health and safety risks.[49]

According to JPD’s force data, nearly 20% of all taser usages was against individuals who officers characterized in their reports as not resisting or demonstrating only low-level resistance.

JPD officers unlawfully use tasers to gain compliance. In some cases, active resistance or an imminent threat can make the use of tasers proportionate if taser deployment is reasonably necessary to arrest the person. In others cases, however, officers use tasers solely to gain compliance without a commensurate threat or where this level of force is not warranted. For example, officers use tasers in incidents that arise from non-violent offenses such as driving without a license and crossing the street unsafely. Officers also use tasers on people lying on the ground demonstrating only low-level resistance, often because the person would not submit to handcuffs—not because they posed an immediate danger.[50] According to JPD’s force data, nearly 20% of all taser usage was against individuals who officers characterized in their reports as not resisting or demonstrating only low-level resistance.

A 2023 incident illustrates some of these concerns. Officers stopped a car at a gas station for an expired registration. The officers spotted what they believed to be narcotics, and one officer shouted that he would “break [the] motherf***ing jaw” of the Black driver if he did not exit the car. The officers attempted to pull the driver out by his wrists, but he did not comply. When the officers let go, the man sat still with his hands up, repeatedly asking why he was being arrested. An officer discharged a taser at the man’s bare chest. Moments later, while the man’s hands were still raised, the officer tased him again. The officers dragged the man out of the car to the ground. While the driver sat motionless and while two officers tried to put his hands behind his back, the officer tased him a third time. After 20 seconds, while officers held the man on the ground, the officer tased him a fourth time. The total length of taser deployment across all uses exceeded the 15-second maximum that the manufacturer recommends for safe use in the absence of a reasonably perceived immediate threat.[51] These repeated deployments were unreasonable: the man was not suspected of a violent offense, and at the time he was tased, he was not posing a threat or attempting to flee. Yet the reviewing supervisor found the force justified and the force review panel did not raise any concerns.

In a 2019 incident, two officers responded to a call for a welfare check regarding a naked man at a self-storage facility. The officers reported that “it was immediately apparent” that the man, who was Black, “was under the influence of a controlled substance.” Officers attempted to engage with him, but his answers were evasive. According to officer reports, an officer took the man to the ground because he tried to flee and refused to put his hands behind his back, and then tased him in the chest because he was actively resisting. The taser video of the incident, however, shows the man laying passively on the ground, not actively resisting. The officer then deployed the taser a second time but missed. An officer then struck the man in his face with his hand. The officers’ reports concede that the man did not attempt to fight them. The video indicates that officers tased the man twice simply to overcome passive resistance and to gain compliance with the officers’ verbal commands. Taken together, this evidence indicates that this welfare check ended with an intoxicated man, who posed no threat, being tased and punched in the head. This significant use of force was disproportionate to the offense of public indecency. The reviewing supervisor did not attempt to reconcile the discrepancies between the video and the officers’ accounts or identify any concerns with the use of force. The force review panel’s recommendation for this incident is missing.[52]

In a 2021 incident, an officer used a taser on an individual at an elevated height, risking death or serious bodily harm. Tasing someone in an elevated position risks a dangerous fall,[53] and JPD trains officers not to use tasers in that circumstance. Despite this training and policy, officers tased a person who was climbing out of a second-story window. Officers responded to a call about sounds from an apartment that was supposed to be vacant. In the apartment, the officers encountered a Black man in his underwear hiding behind a couch. According to their reports, officers had probable cause to arrest the man for domestic battery. The officers pointed their guns and tasers at the man, who threatened to kill himself by jumping out a window. As two officers tried to arrest him, he pulled away. The officers deployed their tasers as the man’s body was partway through the window, creating a risk that he would fall two stories, causing serious injury or death. Although the man was trying to avoid arrest, he did not pose a threat to officers. Fortunately, the tasers had limited effect and the man survived the fall, but as he fled, he began climbing over a fence, and another officer deployed a taser two more times. These taser uses against a person at an elevated height who posed no imminent threat created a substantial risk of death or serious bodily harm and constituted an unlawful use of force. Neither the supervisory review chain nor the force review panel identified any problems with the incident.

Head strikes and punches to the face and head

JPD’s pattern of unlawful force includes the use of head strikes, which officers resort to quickly and in unwarranted situations. Head strikes with a closed fist or an object are serious and potentially lethal uses of force.[54] In addition, punching a person who is on the ground can cause the person’s head to strike a hard surface and carries some of the same risks as a baton strike to the head, which is considered lethal force.[55] Punches to the head and face should be used only in self-defense or defense of another, not to gain compliance in handcuffing.[56]

JPD policy notes that “[a] blow to the head or neck area with a police baton could cause death or great bodily harm” but does not expressly address when head strikes are permitted. Although JPD does not train officers to use head strikes as a distraction technique, it does not prohibit or discourage doing so. In some instances, officers punch people in the face and head to gain compliance, even when they have not committed a violent offense or pose little threat of harm.

In some instances, officers punch people in the face and head to gain compliance, even when they have not committed a violent offense or pose little threat of harm.

In a 2019 incident, officers used an unjustified head strike against a 16-year-old Latino youth. Officers found him sitting on the couch following a call alleging he had hit his mother. The officers told him to stand and place his arms behind his back.[57] When he did not immediately comply, they grabbed his arm. By quickly resorting to physical control after just one command, the officers unnecessarily escalated the encounter. Then, because the teen “tensed up” and did not cooperate with being handcuffed, an officer punched him in the face to gain compliance. Although some force may have been appropriate to make the arrest, using a head strike against a teenager who was not threatening two adult male officers was unnecessary and excessive. Moreover, the officers’ stated justification was that the teen’s bulky coat could have been concealing a weapon—a speculative explanation that does not justify the tactic or the force used. The supervisor and the force review panel approved the use of force and did not identify any concerns.

In another incident from 2018, an officer used an unlawful head strike while arresting a Black man after pulling him over for failing to use a turn signal. Officers determined that he had two outstanding traffic warrants and told him he was under arrest. The man, who was intoxicated, failed to comply by tensing up and pulling his arms away, and the officers struck him repeatedly in the legs, torso, and side of his face, causing a laceration. The officers then brought him to the ground where they punched him in the ribs before taking him into custody. Because the man was suspected of non-violent offenses and his resistance was limited to pulling away from the officers, the head strike was not proportionate, particularly as four officers were present to control a single arrestee. The total amount of force used, including the head strike, was unreasonable under the circumstances, but the supervisory review chain and force review panel did not identify any problems with this incident.

Other bodily force types

JPD’s pattern of excessive force also includes unlawful punching, kicking, or kneeing people on other parts of their bodies. For example, in a 2019 case, an officer approached a man sitting on the front stairs of a house while responding to a call about a “suspicious” Black man. The officer’s report states that the man pushed him, but video shows that the man made only minor contact with the officer’s arm before the officer shoved him against the concrete steps. Video also refutes the officer’s reported claim that the man was reaching for his waistband when the officer shoved him. A fight ensued, with the officer putting the man in a headlock and taking him to the ground as another officer arrived to assist. The officers deployed pepper spray in the man’s face and punched him several times on his face and body. Although some force became reasonably necessary after the officer escalated the altercation, both officers continued punching the man after he was subdued, lying on the ground, and no longer a threat. The officers’ repeated punches of an arrestee passively lying on the ground violated the Fourth Amendment, especially because the officer provoked and escalated the confrontation. The supervisor found the force to be objectively reasonable, reporting incorrectly that the man provoked the encounter when he “suddenly jumped up and shoved” the officer. The only concern identified by the force review panel was that one of the officers was not wearing their vest or microphone.

Takedowns are JPD’s most frequently reported type of force.

JPD’s pattern of unlawful force also includes the use of takedowns, in which officers tackle a person or bring them to the ground. Takedowns are JPD’s most frequently reported type of force. But under JPD policy, the term “takedown” is not defined, and a takedown that does not result in injury or an alleged injury is not a use of force that triggers supervisory review. This limitation sends the message that takedowns are not a big deal and creates a gap in policy that may prevent JPD from identifying problematic takedowns—including several that we identified as unreasonable—or opportunities to use de-escalation more effectively.[58]

In a case from 2021, an officer performed a takedown after a vehicle pursuit. The driver, a White male, exited the car at gunpoint and was complying with the officer’s commands to walk backwards with his hands raised above his head. Once the driver reached the officer’s vehicle, the officer kneed the driver in the back of his leg to bring him to the ground. Although this use of force was unnecessary and unlawful, JPD did not conduct a supervisory review of the incident. This review could have identified that the officer’s stated justifications for the takedown (that he feared the driver was armed and that he heard another car drive up to the scene) were insufficient and contradicted by the squad car video, which shows that the driver was not posing a threat and suggests that the officer was not aware of the second vehicle until after the takedown.

In another case from 2019, an officer performed a takedown of a Black woman who refused officers’ orders to step back amid a “chaotic” crowd participating in a community prayer vigil. The officer’s report states that he pushed the woman to the ground after she swung at him. Videos of the encounter contradict the officer’s version of events. The videos show that, within fifteen seconds of arriving on scene, the officer approached the crowd and tackled the woman even though she was not physically threatening him. The force was unnecessary and excessive. JPD sought obstructing and aggravated assault charges against the woman, which a judge later dismissed.[59] Because the woman alleged that she was injured, a supervisor reviewed the force. The supervisor relied on officers’ statements to find the takedown reasonable.[60] After later viewing video of the incident, the supervisor found the force to be “unnecessary and excessive” and submitted a complaint to Internal Affairs.[61]

Firearms

Our review identified several areas of concern with JPD’s policies and practices for pointing firearms. Although we do not separately find that JPD engages in a pattern or practice of unlawfully pointing firearms, we determined that JPD fails to give officers sufficient guidance about when they may point their firearms and does not require officers to properly document or report such incidents.

Pointing a gun at a person constitutes a seizure because it carries an implicit threat of deadly force.[62] For that reason, pointing a gun at someone who presents no danger is unreasonable and violates the Fourth Amendment.[63] While officers can reasonably draw or point their firearms to protect their safety under appropriate circumstances, drawing or exhibiting firearms can also create tactical risks by limiting an officer’s alternatives for controlling a situation, in addition to the possibility of death or serious injury through accidental discharge.[64] And being held at gunpoint by police can unnecessarily traumatize community members. In one lawsuit alleging illegal gun-pointing by JPD officers, residents of Joliet described ongoing anxiety and nightmares about their terror at being forced out of bed at gunpoint before dawn: “Being awakened by [officers] pointing rifles directly in their faces at point blank range traumatized plaintiffs, especially the children . . . . Ever since the incident, plaintiffs have continued to re-live, in various ways, how terrified they were that day.”[65]

Law enforcement agencies should provide clear guidance on pointing firearms and require adequate documentation of these incidents.

For these reasons, law enforcement agencies should provide clear guidance on pointing firearms and require adequate documentation of these incidents. JPD’s use of force policies, however, impose few limitations on when officers can draw, exhibit, or point their firearms. The relevant policy vaguely states that “[e]xcept for maintenance, inspection, or training, police officers will not draw or exhibit their firearm unless circumstances create a reasonable cause to believe that it may be necessary to use the firearm in conformance with this order.” This broad language fails to specifically instruct officers about when, as a practical matter, they may draw or exhibit their firearms, and it does not address the act of firearm pointing at all.

JPD policy is also deficient with respect to documenting incidents of gun-pointing. Instead of following the procedure for reporting most uses of force (i.e., submitting a written report explaining the circumstances and justification for the force), officers who point guns at people are required only to notify dispatch and state “how many people [they] directly pointed [their] firearm at.”[66] As a result, gun-pointing can escape the usual documentation, supervisory review, and force review panel processes. This exceptional treatment in JPD’s policy creates the false impression that pointing a firearm is not a significant event and need not be justified under the circumstances. It also inhibits the Department’s ability to assess whether officers are following the law.

Although we do not separately find that JPD has a pattern of unlawful gun-pointing (owing in part to JPD’s failure to require written reports of these incidents), we did identify instances in which officers pointed guns in a manner that escalated the encounter and created unnecessary danger. In these cases, JPD also failed to take appropriate actions to address the problematic conduct. These incidents underscore the importance of developing detailed policies that identify how, when, and why officers are permitted point firearms, as well as improving procedures for reporting gun-pointing to facilitate meaningful oversight.

In one 2023 incident, officers pulled over a car for failing to use a turn signal. The officers suspected that the Black male driver had been the subject of an earlier domestic violence call in which he allegedly possessed a handgun. During their initial conversation, the officers did not have their guns drawn and the driver did not act in a threatening manner; his hands were visibly raised, he did not speak or act aggressively, and he was not reaching around inside the vehicle. But when the driver repeatedly failed to identify himself, the officer apparently became impatient and escalated the encounter by suddenly drawing his gun and pointing it at the driver before pulling him out of the car and taking him forcibly to the ground. Although the officer had reason to believe that the driver could have been in possession of a handgun (he ultimately turned out to be unarmed), it was not reasonable to effectuate a seizure with a threat of deadly force against a subject who was only passively refusing to comply with orders. Under these circumstances, pointing a weapon was unnecessary and created unjustified risks. Despite these tactical errors, the supervisory chain of review and the force review panel approved the officers’ use of force.

The baseball field at Joliet Catholic Academy

JPD’s Internal Affairs unit also failed to properly investigate this incident. The investigator did not initiate a formal investigation into the driver’s complaint or interview the driver or the officer. Instead, he conducted an informal inquiry, reviewed existing videos and reports, and exonerated the officer without conducting a thorough or adequate analysis of the case. The investigator’s finding that “the drawing of the [officer’s] firearm appeared to be reasonable based on the fact [sic] and circumstances” is vague, conclusory, and based on insufficient evidence. For example, the investigator apparently accepted the officer’s statement that he “fear[ed] that he could be battered,” contrary to video footage that showed the driver only passively resisting. In addition, the report improperly conflated the decision to draw a firearm with the decision to point the firearm directly at the driver. The investigator also failed to consider the officer’s central role in escalating the incident, writing that “[t]he encounter . . . was escalated when [the driver] refused to identify himself.” These deficiencies underscore the need for detailed policies governing firearm-pointing to ensure that meaningful standards govern the supervisory and administrative review of such incidents.

Problems with JPD’s accountability system also undermine the review of gun-pointing incidents. For example, JPD failed to sufficiently investigate allegations that officers unnecessarily pointed guns at a Black 12-year-old child. In 2018, officers executed a search warrant at a house to look for “proceeds from a credit card fraud case.” About a dozen officers entered the home with weapons drawn. At the time, the only people home were a woman and her 12-year-old grandson. The boy’s mother filed a complaint alleging that several officers pointed their guns directly at the boy as he came down the stairs shirtless. But the Internal Affairs investigation was not thorough or objective. The investigator did not interview any of the officers who allegedly pointed their guns, instead relying on an interview with a supervisor who claimed that the officers held their guns at “low ready” (i.e., at a 45-degree angle toward the ground). The investigator accepted this account without conducting any interviews of the accused officers and discredited (without explanation) the detailed statements by both the boy and his grandmother. As a result, Internal Affairs concluded that the allegations were “unfounded.”

JPD uses unlawful force against teenagers

JPD also uses unreasonable force and unnecessarily aggressive tactics against teenagers. “Research on adolescent brain, cognitive, and psychosocial development” shows that “adolescents are fundamentally different from adults in ways that warrant their differential treatment in the justice system.”[67] Courts recognize that these developmental and behavioral differences impact how youth are treated and that age can be relevant to whether force is reasonable.[68] Police interactions with youth should be developmentally appropriate and trauma-informed.[69]

JPD’s force policies and de-escalation trainings have no youth-specific guidance.

JPD’s “Juvenile Offenders” policy directs officers to “use the least forceful alternative” with youth under 18, which may involve “informal resolution, such as verbal warning and/or notification of parents,” citations for vehicle violations, or compliance tickets and juvenile contact forms. However, JPD’s force policies and de-escalation trainings have no youth-specific guidance. One officer expressed concern about the general lack of training and sensitivity that patrol officers have when dealing with youth. The lack of youth-specific guidance and training was apparent in the force files we reviewed and the experiences that community members shared.

Between 2017 and 2023, 14.4% of JPD’s uses of force were against people ages 18 or younger. In the incidents of unlawful force against teenagers that we reviewed, JPD officers often failed to adjust their responses to reflect the unique context of these interactions.[70]

In one 2020 incident, officers attempted to stop a vehicle whose description was linked to an in-progress armed burglary. The driver pulled over after a 15-mph pursuit that lasted seven blocks. Officers asked the Black teenage driver to exit the car. He initially refused, stating that he was not getting out because the officers had their guns out. The teen eventually exited but refused demands to put his hands up so that he could record the incident on his phone. The teen eventually complied and apologized. While his hands were raised, officers pepper sprayed him, pushed him against the car, and took him to the ground. An officer put his knee on the teen’s back while other officers pointed guns at him. At the time officers used force, the teen was compliant and apologetic. Neither the supervisors nor the force review panel raised any concerns.

JPD officers do not intervene to prevent excessive force

Under the U.S. Constitution, state law, and JPD policy, police officers have a duty to intervene to prevent other officers from violating community members’ constitutional rights. This duty applies in the force context whenever an officer is present and (1) has reason to know that excessive force is being used, and (2) has a realistic opportunity to prevent the harm from occurring.[71] A “realistic opportunity” means a “chance to warn the officer using excessive force to stop.”[72] Each officer has an independent duty to act, regardless of rank or the number of other officers present.[73]

Officers have had a legal duty to intervene throughout our investigation.[74] In 2021, Illinois adopted this pre-existing constitutional duty into state law and added a reporting requirement: officers must report a summary of intervention actions taken within five days of the incident.[75] State law also prohibits retaliation or discipline against an officer for intervening.[76] Since 2022, the Illinois Law Enforcement Training Standards Board has also had discretionary authority to decertify a police officer if it finds the officer failed to intervene when required.[77]

In May 2022, JPD updated its force policy to require members to notify a supervisor within five days if another officer engaged in unreasonable force, or if the member becomes “aware of any violation of departmental policy, state/provincial or federal law, or local ordinance.” It is commendable that JPD’s intervention requirements apply to violations of both law and Department policy.

The investigative team identified numerous unreasonable uses of force, but there were almost no instances of any officer intervening.

Although JPD’s policy on the duty to intervene incorporates legal obligations and best practices, the evidence we reviewed raises significant concerns about officers fulfilling this duty—and supervisors allowing this failure to persist. The investigative team identified numerous unreasonable uses of force, but there were almost no instances of any officer intervening. For example:

- Multiple officers watched an officer use disproportionate force on an unarmed Black man who refused to get out of his car. No one intervened as the officer slammed the man’s head into the car frame and then tased him, yelling “YEAH!” before tasing him a second time. Instead, a bystander officer asked, “How’d that feel?”[78]

- Multiple officers failed to step in when an officer unreasonably tased a Black man who refused to get out of his car, even though the man had obeyed orders to open his windows, turn off the car, drop his keys outside the car, and keep his hands outside the window.[79]

Neither the reviewing supervisors nor the force review panel identified any concerns in these incidents. The duty to intervene is predicated on officers’ ability to recognize when a use of force seems unreasonable. Yet, as discussed elsewhere in this Report, officers have little cause to believe that their supervisors will find any use of force unreasonable or out of policy.[80]

Between 2017 and 2022, only one of more than two dozen Internal Affairs cases involving a use of force allegation yielded an investigation into a violation of the duty to intervene. Following an investigation of a 2018 incident involving an officer unreasonably lifting a man by the handcuffs and pulling him backwards down several steps,[81] Internal Affairs opened an investigation against two officers and a sergeant who witnessed the events but did not intervene or report the force. The two officers claimed they did not see the third officer’s actions, despite video showing all three officers standing next to one another when the force occurred. From across the parking lot, the sergeant could hear the arrestee’s screams and report what occurred. Although Internal Affairs found that the sergeant should have intervened, JPD took the two officers at their word and did not sustain the complaints against them, despite video disproving their statements. No other incidents in the five-year period prompted an inquiry—by a reviewing supervisor, the force review panel, or Internal Affairs—into a failure to intervene.

JPD’s lack of meaningful supervision and discipline for unreasonable force and failure to intervene sends a powerful message. One officer stated that “no one is scared . . . because at most you’ll get a few days suspension.” Conversely, officers do fear retaliation for intervening or reporting on other officers. This fear, while not unanimous, was raised repeatedly. An officer shared that he has witnessed excessive force and that there have been times when he felt like he should say something, but he did not because of an “unwritten code” to stay silent.[82] Another officer confided, “What if I see another officer acting unprofessionally and I pull him to the side, and then I get told on? What if I see a sergeant doing something, will I get fired? You have to weigh those options.”

Factors that Contribute to JPD’s Pattern of Unlawful Force

JPD’s pattern of unlawful uses of force can be traced to the Department’s policies and training, its failure to meaningfully supervise, review, or hold officers accountable, and a culture that discourages officers from intervening or reporting behavior that may violate policy or the law. JPD must provide officers with policies, training, and supervision to enable officers to do their job lawfully, safely, and in an unbiased manner that protects the public and builds trust.

JPD’s inadequate supervision, force review, and accountability systems enable patterns of unlawful and problematic force

JPD’s pattern of unreasonable force is enabled, encouraged, or tacitly condoned by gaps in JPD’s supervisory and force review systems. On paper, JPD policy requires several levels of review of force: most force is reviewed by a supervisor, the watch commander, a deputy chief, and either a non-deadly or deadly force review panel. In practice, meaningful review is illusory. At all stages, reviewers tend to focus on what can be justified (plausibly or not) rather than whether the force was reasonable.[83]

At all stages, reviewers tend to focus on what can be justified (plausibly or not) rather than whether the force was reasonable.

JPD consistently fails to identify and correct unreasonable force. Between 2018 and 2022, supervisors found more than 99% of the force they reviewed justified. And each of JPD’s annual use of force summaries for these years state that “ALL incidents continue to be found within policy.” JPD’s inadequate and ineffective review can be attributed, in part, to:

- deficiencies in JPD policy;

- deficient supervisory investigations of force incidents;

- failure to reconcile inconsistencies in reports and conflicting video evidence;

- failure to address policy violations and tactical concerns; and

- inadequate record-keeping.

JPD’s chain of review also misses valuable opportunities to improve policies, tactics, and training. These deficiencies have serious consequences. A failure to identify and address excessive force and other problematic conduct amounts to tacit approval and allows it to continue.

JPD’s supervisory review is inadequate and rarely finds force unreasonable

JPD policy requires officers to notify a supervisor for most reportable uses of force.[84] Supervisors conduct a preliminary investigation on scene, document all their investigative actions in a written Supervisor Inquiry, and assess whether the force was objectively reasonable.[85] If a supervisor believes force was unreasonable or constitutes possible misconduct, they are supposed to file a complaint with Internal Affairs. JPD supervisory and command staff shared that if a supervisor identifies a minor concern in their review, they could take immediate corrective action by speaking with the officer.

All reportable uses of force that require supervisory review are then reviewed by the watch commander and Deputy Chief of Operations. Both the watch commander and Deputy Chief of Operations review all force reports and Supervisor Inquiries. JPD policy requires them to assess if the force was objectively reasonable; whether JPD’s policies, tactics, training, and equipment were effective; and whether JPD’s training coordinator should be notified of any concerns.[86] They must document any concerns in a memorandum to the Deputy Chief of Administration, who oversees Internal Affairs. Despite these layers, meaningful review rarely occurs.

JPD’s supervisory review is inadequate at all levels. During our period of review, front-line supervisors rarely raised a concern that force was excessive. In only two of the numerous unlawful uses of force identified by the investigative team did a supervisor flag a potential concern. These two incidents are described below:

- In the 2018 incident involving officers lifting a man by his handcuffs, the supervisor said: “At this time, I am unable to determine if [the officers’] actions are justified.” The force review panel referred the incident to Internal Affairs.

- In the 2019 incident involving an officer tackling a woman, the supervisor initially approved the force. After videos of the incident became available, the watch commander referred the incident back to the supervisor who then concluded that the force was “unnecessary and excessive based on what [he] observed on video.” The supervisor then submitted a complaint to Internal Affairs.

Beyond the 2019 incident above, we saw no evidence that a watch commander or the Deputy Chief of Operations identified any excessive force concerns or referred force to Internal Affairs for any of the instances of unreasonable force that we reviewed.

Supervisors’ deficient preliminary force investigations contribute to the oversight failure. Many of the Supervisor Inquiries we reviewed reflect perfunctory investigations, taking officers’ version of events at face value. We also observed some failures to document meaningful efforts to collect critical evidence (such as witness statements, videos, or photos), and whether they reviewed available evidence (such as taser reports that verify the number of times a taser was used or video from tasers, body-worn cameras, or squad car cameras).[87] For example, in a 2019 incident, a supervisor reported that there were multiple security cameras that might have captured officers’ force, but he could not access them because the business was closed at the time. There is no indication that he made additional efforts to obtain the video (and the videos are not in JPD’s evidence management system). The supervisor also failed to acknowledge the existence of a taser video that showed portions of the uses of force.[88]

Many of the Supervisor Inquiries we reviewed reflect perfunctory investigations, taking officers’ version of events at face value.

Supervisors’ failure to document efforts to collect and review evidence is particularly concerning because we identified incidents where video contradicted officers’ version of events. We discuss some of these in other sections, and note here that the supervisors consistently failed to reconcile (and often did not even acknowledge) conflicting video evidence. These and other examples suggest that supervisors routinely fail to review material evidence,[89] do not recognize unlawful or problematic force when they see it, or ignore its content.

We also identified unreconciled inconsistencies in officer reports. In some cases, the reports were internally inconsistent or conflicted with other officers’ reports on key facts, such as the number of persons who resisted, the number of officers present, the type of resistance officers faced, or the type of force used. In other cases, the Supervisor Inquiry conflicted with officers’ reports in material ways—such as the type, severity, and reason why force was used—or failed to review all of the instances of force used. For example, in a 2020 encounter where one officer tased a man and a second officer punched him in the face,[90] the supervisor addressed the propriety of only the taser use. Though both the officers’ force report and case report stated that he punched the man in the face, the supervisor failed to mention, much less review, the force. When we asked a group of lieutenants to review the reports associated with this incident, none raised that the punch had not been reviewed. This is not meant to reflect poorly on the supervisor who completed the underlying review nor the lieutenants. Rather, it indicates a deficiency in supervisory training for reviewing force, supervisory oversight, and/or a flaw in JPD’s policy, which does not explicitly require supervisors to separately review each use of force within an incident.

In addition to flawed preliminary investigations, we identified other supervisory concerns. For example, we found clear policy violations, particularly involving taser usage, that appear to have gone unchecked. We also observed some instances of peer review (where the reviewing supervisor is of the same rank as the person who used force) and of supervisors involved in the underlying incident reviewing the force used, both practices that JPD policy fails to prohibit.

JPD policy also treats the “objective reasonableness” standard as the only benchmark for the supervisory review process. For example, JPD does not require supervisors to assess whether force could have been avoided or whether the officer could have used de-escalation tactics.[91] Nor does it require supervisors to document whether they addressed concerning tactics or offered guidance that might have reduced the need for, or amount of, force used. During a focus group, sergeants said that they typically address tactical deficiencies through informal, undocumented training, as there is “always…a learning point.” While it is good that these conversations take place, supervisors’ failure to document these concerns impedes the Department’s ability to identify officers who frequently use flawed tactics and to identify pervasive deficiencies that may require Department-wide training.

JPD’s supervisory review is an exercise in justification. Supervisors consistently approve unlawful force, finding even egregious force justified.

JPD’s supervisory review is an exercise in justification. Supervisors consistently approve unlawful force, finding even egregious force justified. The insufficient supervisory review extends up the command chain. We identified only one instance of a watch commander or the Deputy Chief of Operations flagging a potential concern.[92] The JPD lieutenants we interviewed indicated that they had never seen an unjustified use of force and that, at most, they have sent back force reports to be corrected for clarity, completeness, or accuracy.[93] The cursory oversight by high-ranking staff enables problematic patterns in uses of force to continue unchecked. The following two incidents illustrate many of these supervisory concerns.

In a 2022 incident, officers attempted to stop a Black man who was sleeping in his car in a public park after dark. The man drove away and police pursued him at roughly 10 miles per hour for two minutes before terminating the pursuit. Later that night, officers again found him in the park sleeping in his car. They boxed his car in, approaching him with guns drawn. When the man refused officers’ orders to exit the vehicle, officers broke both the passenger’s and driver’s side windows. As they tried to extract him from the car, one officer grabbed the man’s head and, using the momentum of his body weight, repeatedly slammed his head against the inside door frame. The same officer proceeded to tase the man in the back. The man then rolled out of the car and onto the ground, and the officer tased him a second time while yelling “YEAH!”

Neither the officer’s force report nor the Supervisor Inquiry acknowledge that the officer slammed the man’s head multiple times into the door frame. The supervisor found both taser uses justified. No one in the supervisory review chain identified any policy violations, including tasing a man on the ground who was not physically threatening and cheering during the use of force. And there is no documentation to suggest that they identified any concerns or referred this incident to Internal Affairs[94] or that they provided the officers any guidance on tactical considerations, de-escalation techniques, or the duty to intervene.

In a 2021 incident, officers broke up a physical altercation between two men. One of the men was “combative” and “hostile” and under the influence of PCP. The man reportedly “tensed up” and pulled away when an officer attempted to handcuff him, prompting the officer to knee the man in the leg, taking him to the ground. A second officer transported the man to the station. During processing, the handcuffed man reportedly turned toward this officer and shouted obscenities at him. The officer reported that he feared that the man might try to hurt him, so the officer pushed the man’s chest. The man fell backwards and struck the back of his head on a metal bench. Officers called an ambulance to address the man’s PCP intoxication and to examine for any head injuries. The man was taken to a hospital where he was given a CT scan of his head.

The supervisor only reviewed and approved the knee strike by the first officer. While the objective reasonableness of this force is questionable, the supervisor failed to even acknowledge the second officer’s force. JPD’s booking area cameras likely captured this force, but the supervisor made no effort to obtain it. The Supervisor Inquiry states that the man was sent to the hospital for a forehead injury he sustained during the first altercation, which contradicts the second officer’s report. It is unclear why the supervisor failed to review the second use of force, but the officer’s push could be considered touch pressure or a takedown, neither of which require supervisory review under JPD policy if there was no injury or alleged injury. Although the CT scan showed no swelling or bleeding in the brain, the reviewing supervisor, watch commander, and Deputy Chief failed in their obligation to review a use of force against a restrained person that resulted in him hitting his head on a metal bench and going to the hospital to determine whether the force caused bleeding in his brain.

JPD’s non-deadly force review panel’s oversight is inadequate and rarely finds force unreasonable

JPD’s force review panel conducts the final layer of review of reportable non-deadly force. Per policy, the panel includes a lieutenant, the training coordinator, the range master, a defensive tactics instructor, a taser instructor (who is also a member of the supervisors’ union), and a member of the officers’ union. As an initial matter, including union representatives creates a conflict of interest because they have a duty to defend their members’ interests.[95]

The panel meets twice a month and reviews all reportable non-deadly force that occurred since its last meeting. The panel’s review includes assessing whether the force was objectively reasonable and adhered to policy and training, and whether there are policy, training, weapons, or equipment concerns that need to be addressed. The panel may return the force report to the officer’s immediate supervisor to make corrections or conduct further investigation. The panel may also refer any incident to Internal Affairs. After its review, JPD policy requires the panel to submit a report to the Chief detailing its findings, the reports the panel reviewed, and any recommended actions to be taken.

Similar to the supervisory chain of review, the force review panel signs off on most force without making any meaningful effort to assess whether the force was justified or whether officers adhered to policy and training.

Similar to the supervisory chain of review, the force review panel signs off on most force without making any meaningful effort to assess whether the force was justified or whether officers adhered to policy and training. The panel almost never makes a substantive recommendation (such as recommending remedial training or referring to Internal Affairs for investigation). It also has inadequate record keeping, which further contributes to its ineffective review.

We observed several panel meetings during our investigation. In some instances, the panel members did not review all relevant video or photo evidence.[96] The panel often drew conclusions before the end of the video or file review and narrated justifications of the force as the video played. Panel members rarely discussed whether force was necessary in the first instance, whether a lower level of force could have been used, or whether de-escalation or crisis intervention techniques could have been used. We observed concerning tactics and potential policy violations that the panel failed to acknowledge, let alone address. Most concerning was the panel’s failure to identify or meaningfully discuss clearly unlawful force, including the 2022 incident that involved force used against a Black man sleeping in his car and the 2023 incident that involved a Black man being repeatedly tased at a gas station.

We also analyzed every panel recommendation from 2017 through 2022. The panel logged “None” or “No recommendation” nearly 85% of the time. JPD was unable to find panel recommendations for about 5% of the force incidents during this period.[97] The panel made a substantive recommendation (such as remedial training, shift-level counseling, or referral to Internal Affairs) or requested additional review or investigatory steps in only 3% of the force incidents it reviewed. Most of the remaining panel recommendations were vague or trivial.[98]

Of the numerous uses of force that the investigative team found unlawful, the panel made a substantive recommendation for only around 10% of these incidents. And of the unlawful uses of force we describe in this Report, which represent only a fraction of the total unlawful uses of force we identified, the panel made only three substantive recommendations following its review. The panel referred only two cases to Internal Affairs: the 2019 incident involving an officer who slapped a man in the face after he fell to the ground,[99] and the 2018 incident involving an officer dragging an arrestee by the handcuffs.[100] In the 2019 case involving an officer who shoved a man against concrete steps, the panel recommended that a sergeant counsel the officer for not wearing a vest and microphone.