JPD’s Flawed Accountability Systems Contribute to Patterns of Unlawful Policing

JPD’s accountability systems fail to adequately detect, investigate, respond to, and document misconduct. These failures directly contribute to patterns of unlawful policing. As discussed in the preceding sections, JPD engages in practices that include unlawful uses of force, discriminatory policing, and failure to adequately respond to gender-based violence. Each of these practices results from the Department’s failure to properly respond to misconduct and appropriately consider disciplinary history in the promotion process. These failures of accountability contribute to a culture within JPD that tolerates or ignores serious wrongdoing, while eroding relationships between the Department and the community it serves.

Overview of JPD’s Internal Affairs and Accountability Systems

JPD’s Internal Affairs unit conducts most of the Department’s administrative investigations into alleged misconduct. Internal Affairs is staffed by a sergeant and a lieutenant who share responsibility for conducting and reviewing investigations. Members of Internal Affairs report to the Deputy Chief of Administration and the Chief of Police.

Administrative investigations begin with a complaint, which can originate either internally from Department members or externally from community members. Upon receiving a complaint, Internal Affairs conducts a preliminary investigation, usually reviewing police reports and body-worn and squad car videos, and attempting to contact the complainant. Investigators then place complaints into one of three classifications: formal complaints, informal complaints, and informal inquiries. These classifications generally dictate how thorough the investigation will be, with typically little or no fact-finding occurring for complaints classified as informal.

JPD’s complaint classifications generally dictate how thorough the investigation will be, with typically little or no fact-finding occurring for complaints classified as informal.

In formal investigations, Internal Affairs investigators generally begin by gathering evidence such as police reports, videos, and photographs, and attempting to contact the complainant to schedule an interview. In some cases, investigators may try to interview non-Department witnesses. The interrogation of the accused officer is usually one of the last steps in the investigation. The investigators audio-record all interviews and interrogations in formal investigations, except for non-Department complainants and witnesses who decline to be recorded.

Internal Affairs investigators summarize the evidence gathered and factual findings in an investigation report. This typically includes a thorough description of each interview and interrogation. Investigation reports also list a disposition for each of the allegations: sustained, not sustained, unfounded, or exonerated. Internal Affairs can also administratively close cases without a full investigation or a disposition. In some cases, investigators refer complaints to the “shift level,” meaning that the accused Department member’s immediate supervisor is responsible for investigating the complaint and/or counseling or training the officer. Internal Affairs has broad discretion to decide when complaints should be handled at the shift level.

Investigation reports are then submitted to the non-investigating member of Internal Affairs to review and sign off on the recommended dispositions. The Chief reviews all completed formal investigations, and in cases of sustained misconduct, the Chief also makes an initial disciplinary decision, which can include an oral or written reprimand, suspension, or termination. The Chief may also require officers to be counseled by their supervisor or undergo additional training.

After the initial disciplinary decision, Department members have several opportunities to seek to reduce their discipline. Members may request an administrative review hearing with the Chief to present mitigating information, which often results in the Chief reducing the discipline. Sworn officers may also appeal suspensions of more than three days either to an arbitrator under the member’s collective bargaining agreement or to Joliet’s Board of Fire and Police Commissioners.

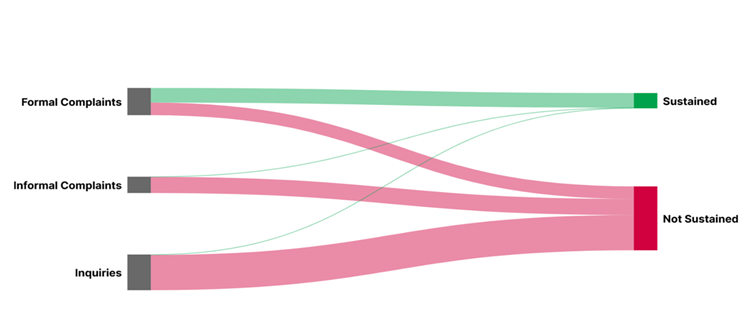

From 2018 through 2022, Internal Affairs received an average of about 77 complaints per year, including complaints that originated both from community members and within the Department. Internal Affairs classified over 34% as formal complaints, about 21% as informal complaints, and about 45% as informal inquiries, which receive the least amount of investigation. In about 19% of cases, Internal Affairs sustained at least one of the allegations, though these sustained dispositions were highly concentrated among internal complaints that originated within the Department. When a Department member initiated a formal complaint, it was sustained nearly 74% of the time, compared to less than 10% for formal complaints submitted directly by community members.[1] Over 95% of the complaints that Internal Affairs sustained between 2018 and 2022 were classified as formal.

Figure 1: Breakdown of Internal Affairs Complaints by Classification & Outcome

Although Internal Affairs investigators conduct most of the Department’s administrative investigations, other parts of the Department share responsibility for identifying and investigating policy violations. Supervisors in all parts of the Department are required to respond to allegations of misconduct. In addition, two force review panels review reportable uses of force,[2] and the Safety Review Board examines traffic collisions and vehicle pursuits. Apart from limited circumstances in which the Safety Review Board conducts more thorough investigations, Internal Affairs is the only unit within JPD that conducts substantial fact-finding—including interrogating accused Department members—to determine whether a policy violation occurred.

Internal Affairs records are stored in the IAPro software program, which also houses JPD’s records of lawsuits, uses of force, vehicle pursuits and crashes, and other Department member data.[3]

Methodology

To investigate JPD’s accountability systems, we reviewed JPD’s accountability policies and met with current and former Internal Affairs personnel. In addition, we conducted an extensive review of files dating from 2018 through 2022, including hundreds of Internal Affairs files documenting the investigation and resolution of misconduct complaints, as well as records of shift-level counseling.[4] In conducting this review, we examined written reports, photographs, video footage, audio recordings of interviews and interrogations, and other evidence relating to allegations of misconduct. We also examined JPD’s promotion practices by reviewing employment files and records relating to the Department’s promotion recommendations, in addition to meeting with representatives of Joliet’s Board of Fire and Police Commissioners.

Throughout this Section, we highlight examples of incidents and investigations that illustrate our findings. These examples are meant only to demonstrate how JPD’s accountability systems operate in practice. Our conclusions are based on a broader review of many cases beyond the ones specifically described in this Report.

JPD Routinely Fails to Hold Department Members Accountable for Misconduct, Contributing to Patterns and Practices of Unlawful Policing

At each step of JPD’s accountability process, we identified serious deficiencies that undermine the reliability and legitimacy of JPD’s response to misconduct. Taken together, these deficiencies prevent JPD from consistently identifying, investigating, and responding to violations of the law and Department policy. The absence of a reliable accountability system is a significant barrier to preventing misconduct and establishing trust with community members.

JPD’s accountability policies are missing necessary detail

JPD’s written directives for Internal Affairs personnel are limited to its Department-wide policies, which include broad definitions and standards that are used in administrative investigations but often do not communicate specific expectations.[5] This absence of detailed written guidelines contributes to inconsistency in how different Internal Affairs investigators handle complaints. Over a five-year period, different investigators used significantly divergent practices in critical areas such as the classification of complaints and the documentation of administrative investigations. For example, investigators have documented informal complaint investigations in various ways, with some writing detailed investigation reports and others noting only basic information in the IAPro database.

Even where the written policy requirements are clear, Internal Affairs investigators often deviate from them. For example, JPD policy defines the circumstances where Internal Affairs investigators may classify a complaint as informal. Investigators told us, however, that they exercise their discretion to classify complaints based on the perceived severity of the allegations—criteria that are not set out in policy.

Even where the written policy requirements are clear, Internal Affairs investigators often deviate from them.

We identified numerous deficiencies in JPD’s accountability policies, including the failure to adequately or comprehensively define:

- the classification of complaints as formal or informal

- criteria for determining whether to investigate anonymous complaints

- the process for investigating allegations of misconduct from civil lawsuits

- procedures for contacting civilian complainants and witnesses

- standards of proof associated with the disposition of allegations

- supervisors’ discretion to handle a complaint through shift-level counseling

- procedures for ensuring consistent, fair, and proportionate discipline

- the process to avoid conflicts of interest in administrative investigations

The problems that result from the absence of clear and specific guidance on these subjects are discussed in greater detail in the sections below.

JPD lacks adequate mechanisms to identify misconduct and encourage reporting

We identified problems affecting JPD’s ability to learn about allegations of misconduct. These barriers affect reporting from both inside and outside the Department.

Community member complaints

In some ways, JPD’s policy for receiving community member complaints accords with best practices. For example, the Department offers community members numerous ways to submit complaints, including by phone, through an online form, or in person at the police station. At the same time, JPD policy specifies that complainants should never be required to appear at the station to submit a complaint. JPD policy also requires Internal Affairs to accept anonymous complaints, and complainants are not required to submit a sworn statement under oath.

Nonetheless, JPD imposes unnecessary barriers for community members who wish to report misconduct. First, the information the Department provides the public about its complaint process is likely to discourage community members from filing complaints. JPD’s website does not prominently display the option to submit a misconduct complaint, and its “File a Complaint” page provides a warning that may discourage community members from reporting:

Filing a false complaint is a crime. If you willfully submit false information, you will be subject to criminal prosecution. Please note your internet protocol (IP) address of any online submission is logged.

JPD’s complaint brochure similarly discourages complaints. It fails to mention the options to submit a complaint anonymously, decline to be interviewed, or schedule the interview at a convenient time and place. Instead, it states that complainants must sign their complaint and suggests that they may have to be interviewed twice, along with another intimidating warning:

If a person is found to have knowingly filed a false complaint against a member of our department, that member may file a civil action suit against him/her. The person filing the false complaint may also be charged with a criminal violation.

Community members who read this warning may conclude that they—not the accused officer—will be the real targets of any investigation.

Ruins of the Joliet Iron and Steel Works

Second, we have concerns that JPD officers may engage in a pattern of discouraging complaints or making it more difficult for community members to submit them. In numerous Internal Affairs files, there was an allegation or evidence that complainants were expressly discouraged from filing a complaint or were told that they would have to go to the police station to do so. In one case, after a community member submitted a complaint of rudeness via email, the Internal Affairs lieutenant called the complainant, who provided the name of the officer involved and details about the incident. The lieutenant told the complainant that her story contradicted the police reports and that she would have to file a “formal complaint.” When she failed to come to the police station, the complaint was classified as informal and the case was closed.

Internal Affairs also lacks transparency in its investigations. JPD does not offer complainants any way to track the status of complaints online, and contrary to Department policy, Internal Affairs investigators do not notify complainants when investigations are delayed. Instead, investigators place the onus on complainants to seek information about the status of their complaints, creating a risk that complainants will assume that JPD has ignored their case.

Department member complaints

We found evidence that JPD officers are often reluctant or unwilling to report even serious misconduct by fellow officers. Interviews with current and former Department members revealed that officers fear professional and social retaliation if they initiate complaints. One officer described how after he expressed support for another officer who reported misconduct, his relationship with his coworkers “splintered.” Another told us that officers who report misconduct risk being “blackballed,” which could include missing out on desirable assignments.

We found evidence that JPD officers are often reluctant or unwilling to report even serious misconduct by fellow officers.

In our review of investigative files, we also found evidence that in some cases peer officers witnessed misconduct (including excessive force) and failed to report it. In these cases, however, Internal Affairs investigators often failed to separately investigate these violations. For example, in one case squad car video revealed that an officer witnessed another officer using likely unlawful and retaliatory force, striking a person in the face as he lay on the ground after a foot pursuit.[6] Although Internal Affairs reviewed the incident to determine whether the officer who struck the person used unlawful force, Internal Affairs did not investigate whether the officer who arrived at the scene violated JPD policy by failing to report the incident. And in rare cases when investigations occur, Internal Affairs often fails to sustain the allegations or impose discipline.[8] The lack of a strong Internal Affairs response likely contributes to a perception among officers that they will not face consequences for failing to report misconduct.[9]

Allegations discovered during administrative investigations

Internal Affairs investigators often fail to properly identify and investigate potential misconduct discovered during administrative investigations. In some cases, videos or other evidence reveal potential policy violations that extend beyond the allegations in the initial complaint, but which are not separately addressed. This includes cases where the investigation indicates that officers failed to report misconduct that they witnessed.

For example, Internal Affairs investigated a complaint about several officers who engaged in wide-ranging harassment of a person at a bar while on duty, including pouring hot sauce down the bar patron’s pants, drawing a penis on his back, and threatening to deploy a taser. This alleged misconduct was so extreme that it caused a recruit officer who was present during the incident to resign from JPD. Internal Affairs sustained allegations of conduct unbecoming, coarse and disrespectful language, and violation of the duty to report. During the investigation, however, Internal Affairs learned that another officer was called to the scene while the misconduct was occurring, but the investigator did not attempt to determine whether that officer failed to intervene to stop the misconduct or to report it to a supervisor. The investigation also uncovered evidence that the involved officers may have engaged in a wider pattern of inappropriate or harassing behavior toward this person in the past, but the Internal Affairs investigator did not follow up on this information.

Internal Affairs investigators often fail to properly identify and investigate potential misconduct discovered during administrative investigations.

In other instances, Department members engage in misconduct relating to the investigation itself, including making false statements or concealing material information. This obstruction of the accountability process is rarely separately investigated. For example, in one case, JPD learned that an officer had been sending sexually explicit text messages to a woman after she reported a sexual assault to the officer. Investigators obtained copies of the messages from the woman’s cell phone, but when they tried to obtain the messages from the officer’s personal cell phone, they had been deleted. Although several allegations against the officer were sustained, JPD did not determine whether the officer had deleted the messages in order to hide his misconduct. The failure to appropriately respond in cases where officers may have concealed or destroyed material information prevents the Department from identifying and disciplining misconduct that affects officers’ credibility.

Investigations by review boards

With respect to uses of force and vehicle pursuits and crashes, Internal Affairs investigators often rely on other review boards within the Department to detect policy violations and refer cases for further investigation. We found evidence, however, that these review boards do not sufficiently identify and report misconduct. For example, JPD’s force review boards (which are discussed in Use of Force) fail to conduct objective, meaningful reviews and often fail to identify potential policy violations.

The Safety Review Board, which reviews both vehicle crashes and vehicle pursuits, has conducted similarly limited reviews, although the nature and extent of its review processes have changed substantially since the start of our investigation. Previously, the Safety Review Board conducted only a limited investigation that assumed that statements made by Department members in their reports were true and that did not attempt to determine whether vehicle pursuits should have been initiated in the first place. More recently, following changes to policy and upgrades to the Department’s case management technology, the Safety Review Board began conducting more thorough analysis and investigation, particularly in cases that could result in more than three days’ suspension. We commend JPD for bolstering these review procedures, though there is not yet sufficient information to determine whether the Safety Review Board’s investigations of misconduct under the revised policy are adequate.

Outside of this limited context, the review boards generally defer to Internal Affairs to conduct any investigations that extend beyond a first-level review of the paperwork and video evidence. But because the boards do not conduct thorough reviews, they rarely identify possible misconduct and therefore generally do not refer any cases to Internal Affairs. This creates a circular problem where Internal Affairs investigators rely on the absence of adverse findings from those boards to justify closing cases without full investigations. In one case, body-worn and squad car camera videos showed officers using potentially unjustified force while removing a driver from a vehicle, including deploying a taser after the driver had already been brought to the ground and was surrounded by many officers. The Internal Affairs investigator conducted a seemingly cursory review of the footage, which he noted “revealed no clear policy violations,” and explained that “the incident was reviewed by the field supervisor and the [force review board] with no recommendations for further review.” As a result, the investigator classified the case as an informal inquiry and closed it without further investigation.

Allegations from criminal prosecutions and civil lawsuits

Internal Affairs rarely investigates allegations of misconduct stemming from criminal proceedings or civil litigation.

Criminal proceedings. Internal Affairs generally learns about information from a criminal investigation or prosecution only if a Department member was the subject of the investigation or prosecution.[10] JPD has no processes in place to identify possible misconduct from criminal cases where JPD officers were investigators or witnesses (for example, when a judge in a criminal case finds that an officer’s statements or reports were not credible or suppresses the results of a search due to lack of probable cause).

JPD has no processes in place to identify possible misconduct from criminal cases where JPD officers were investigators or witnesses.

In one case, multiple officers testified at a criminal hearing in the prosecution of a woman who allegedly assaulted a JPD officer in the moments before he tackled her to the ground.[11] Three of the officers who testified made statements that differed from what they had told Internal Affairs during an administrative investigation. The officer who tackled the woman provided conflicting testimony about the number of verbal instructions he gave the woman before using force. He also suggested that the woman “almost hit [him] in the face,” while his earlier statement to Internal Affairs said only that she “swung her arm towards him possibly in an attempt to knock his hand away” from her shoulder. The other two officers also gave testimony that materially differed from statements in their Internal Affairs interviews regarding what they saw the woman do in the moments before she was tackled. After the hearing, which focused on these inconsistencies and the lack of evidence that the woman had swung at an officer, the judge dismissed the criminal charges. But Internal Affairs never conducted any follow-up investigation to determine if the officers gave intentionally false or misleading statements during the administrative investigation or under oath at the hearing.[12]

Civil litigation. In some instances, JPD learns about allegations of misconduct because a civil lawsuit is filed. But lawsuits alleging misconduct by department members almost never trigger Internal Affairs investigations, even in cases where the City reaches significant financial settlements or judgments. In the cases alleging department member misconduct that the City of Joliet has settled from 2018 to 2023, Internal Affairs never followed up to investigate after the civil case ended,[13] even in cases in which the City paid hundreds of thousands of dollars.

One cause of this failure to investigate is that Internal Affairs almost always delays investigations of the misconduct while a lawsuit is pending, with the consequence that no investigation occurs at all. JPD does not have a policy specifically addressing whether or when Internal Affairs should begin an investigation once the lawsuit is over. In fact, the City often fails to notify Internal Affairs that a civil case has concluded.

These failures prevent Internal Affairs from investigating cases of serious misconduct. For example, in 2021, Joliet paid nearly $120,000 in a case in which a man alleged that a JPD officer had arrested him and slammed him face-first into the rear of an ambulance after he declined to get in it because he did not need medical care. The man alleged that his face struck the corner of a metal box, splitting open his face just under his eye, and that the officer lied in police reports and criminal charging documents to justify the force. After a trial, the jury found in favor of the man. But despite the jury’s verdict and the cost of the judgment and resulting attorneys’ fees, Internal Affairs never investigated the allegations to determine if the officer violated policy.

JPD’s processes for classifying and processing complaints are inconsistent and prevent thorough investigations

Many Internal Affairs investigations are insufficient because complaints are improperly classified as “informal,” even for major alleged policy violations. In other cases, investigators fail to recognize and investigate the most serious allegations in a complaint. These preliminary decisions often dictate the scope of the investigation and can hinder accountability.

Complaint classification

The three categories Internal Affairs uses to classify complaints largely dictate how it handles and resolves the allegations. Unlike the full investigation it conducts for formal complaints, for informal complaints and informal inquiries, Internal Affairs gathers less evidence, produces less detailed documentation, and usually closes cases without determining whether the allegations are true.

This classification decision generally reflects a judgment about the merit of the complaint. Once a complaint is classified as informal, it is extremely unlikely to be sustained; fewer than 5% of complaints that Internal Affairs sustained between 2018 and 2022 were classified as informal. Despite their importance, these classifications are poorly defined in JPD policy, which permits “informal” classifications under a few circumstances, including whenever there is evidence that “the specific act or omission alleged does not amount to employee misconduct.” But there are no written guidelines specifying when or how the investigator should make this determination. As a result, we found a wide variation in how extensively Internal Affairs investigates complaints before classifying them as informal. Although in some instances the preliminary investigation was thorough, in many other cases there are indications that Internal Affairs failed to gather or review evidence that would have been relevant to the classification decision.

Even serious misconduct allegations are classified as informal, precluding meaningful investigation and discipline. These include allegations of excessive force and discriminatory policing/unlawful bias. In one case, a White officer posted an image with overtly racist jokes to his social media account.[14] The investigation report reflects that the Chief and other command staff decided “that the incident would be handled as an Informal Complaint” and the officer would receive shift-level counseling from their supervisor. The investigation report does not include any further explanation for the informal classification, and the officer did not receive any discipline apart from non-punitive counseling.

Even serious misconduct allegations are classified as informal, precluding meaningful investigation and discipline.

JPD classifies complaints as informal for several reasons that prevent thorough investigations of complaints that may have merit:

- Non-cooperative or difficult-to-reach complainants. Nearly a quarter of the informal complaints we reviewed were classified as informal because the complainant either did not follow up or declined to be interviewed. JPD’s policies do not provide guidance about contacting complainants or pursuing investigations if they are not responsive or cooperative. In practice, it is common for Internal Affairs investigators to make just one or two phone call attempts before sending a letter to the complainant notifying them that their case will be closed if they do not respond. In some cases this outreach is sufficient and the investigation cannot be pursued, but in others, investigators close cases even when they have enough information to proceed without further statements from the complainant.

For example, Internal Affairs informally classified and administratively closed a complaint alleging that a youth was arrested and subjected to force in retaliation for recording JPD officers. The investigator did not contact any potential witnesses or involved officers identified in the case report and did not make any attempts to identify squad car or surveillance video from a nearby business. Instead, Internal Affairs classified the complaint as informal without further investigation because the complainant was not home when Internal Affairs tried calling them, and they did not respond to one follow-up email asking for a call back. - Anonymous complaints. Internal Affairs classified every anonymous complaint it received between 2018 and 2022 as informal. JPD’s policy states only that “[t]he nature of the information” provided in an anonymous complaint “will be evaluated to determine an appropriate investigative response.” This open-ended, vague language makes the investigation of anonymous complaints entirely discretionary. In some cases, an informal classification of an anonymous complaint is appropriate because there is not enough information to investigate further. In others, however, Internal Affairs fails to gather available evidence based on information furnished by an anonymous complainant. For example, one anonymous complaint alleged that an officer was holding a beer while on duty and driving a squad car. The complaint attached photographs showing an officer holding an object that could have been a beer bottle. The investigator noted that the photograph showed the officer’s squad car number, but rather than attempting to identify the officer in the photograph, the investigator simply stated that “[i]t was unable to be determined what was in the officer’s hand due to the quality of the picture.” The case was classified as an informal inquiry and closed without a disposition.

- Complainant’s preference. Internal Affairs improperly relies on complainants’ preferences to determine whether to formally investigate. This deference to complainants does not align with basic standards of accountability. Police departments are responsible for holding their members accountable for their behavior regardless of whether complainants request a formal investigation. Yet in more than a quarter of informal complaint files we reviewed, JPD’s Internal Affairs classified the complaint as informal at least in part because the complainant reportedly preferred not to move forward with a formal investigation.[15] In some of these cases, there was sufficient information to allow further investigation or even reach a disposition without a formal complainant interview. Although Internal Affairs personnel informed us that they have discretion to conduct a formal investigation despite the complainant’s preference to proceed informally, they were unable to identify any case in which this actually occurred.

JPD policy also allows supervisors who receive community member complaints to attempt to “resolve the complaint to the satisfaction of the complainant,” meaning that Internal Affairs will not investigate further. The policy does not specify which types of complaints may be “resolved” in this way. The policy language implies that any complaint—no matter how serious—can forego a formal investigation so long as the complainant is satisfied with the supervisor’s response. In that case, the Department would be unable to investigate and discipline even egregious misconduct.

Mischaracterizing or downgrading allegations

Internal Affairs frequently characterizes complaint allegations in ways that minimize the severity of the alleged misconduct. This method of “downgrading” prevents Internal Affairs from properly identifying and addressing the most serious issues raised in a complaint. We identified numerous cases in which Internal Affairs downgraded serious allegations, including in the areas of discriminatory policing, gender bias and gender-based violence, use of force, and other forms of misconduct involving harm to community members.

Internal Affairs frequently characterizes complaint allegations in ways that minimize the severity of the alleged misconduct.

In one case, the complainant alleged in his complaint that an officer entered his home, acted aggressively, threw him into a table, and “took him to the ground.” The Internal Affairs investigator did not expressly address these allegations of unlawful force; instead, the investigation report stated that the complaint alleged only “False Arrest” and “Mishandling of Evidence.” Another complaint alleged that an officer interrogated a youth who was in custody after the youth invoked his Miranda rights. But the Internal Affairs investigator focused exclusively on the fact that the officer had used curse words, characterizing this allegation as a claim that the officer “spoke . . . in an unprofessional manner while in the JPD booking facility.” In IAPro, the complaint was tagged with the sub-classification “improper language.”

Many of JPD’s administrative investigations are not sufficiently thorough or objective

Although some Internal Affairs investigations are detailed and thorough, the quality of investigations varies substantially, even in serious cases that warrant in-depth investigations. Many investigations suffer from problems with the scope of the investigation, deficient evidence-gathering, flawed interview techniques, biases, and delays. We also identified flawed dispositions in a number of cases.

Narrow scope of investigation

Internal Affairs often investigates only some of the alleged misconduct, without addressing significant potential policy violations that form part of the underlying complaint. In addition, Internal Affairs does not consistently investigate all of the Department members who may have committed misconduct in connection with a complaint.

In one case, Internal Affairs investigated an incident in which an officer allegedly conducted an illegal traffic stop. Video of the incident showed that during the stop, officers broke a car window, pulled the driver out of the car, performed a takedown, struck the driver in the legs with a baton, and deployed a taser.[16] Internal Affairs limited its review of this incident to one officer’s conduct during the initial stop and failed to examine the force used by three officers on the scene. In fact, although Internal Affairs obtained a video of the entire encounter, the video was edited into a short clip ending at exactly the moment that the officer reached his arm back to strike the car’s window. Examining the entire incident would have allowed Internal Affairs to address possible policy violations related to breaking the window, use of force (including takedowns, leg strikes, and taser deployment), as well as the officers’ conduct that escalated the interaction.[17]

Freight train approaching railroad yard

In another case, a complainant alleged that when she contacted the Department to ask about having a rape kit completed, the Department member she spoke with was dismissive and rude. When she contacted a supervisor in an attempt to file a complaint, the supervisor did not document the complaint but instead denied that the other Department member had acted improperly, and he attempted to persuade her not to pursue the rape kit. Citing the complainant’s preference to proceed informally, Internal Affairs referred the case for shift-level counseling, stating only that the involved Department members had been “unprofessional” and omitting any reference to the allegation that the supervisor refused to document the complaint, a separate violation of JPD policy.

Gathering evidence

Internal Affairs frequently fails to gather relevant evidence during administrative investigations. In many cases, Internal Affairs does not obtain videos, photos, and other relevant documentation—many of which are readily accessible in the Department’s evidence management system. Internal Affairs also fails to interview complainants, witnesses, and/or accused Department members whose statements are necessary for a thorough or objective investigation. In one instance, Internal Affairs investigated an excessive force allegation for which there were dozens of officers and community members present.[18] The investigator interviewed at least ten Department members but just one community member, and the investigator did not document any efforts to identify or contact other civilians who were at the scene. Though JPD policy requires the investigator to “[c]ontact all complainants and witnesses as soon as possible,” the investigator wrote, “[t]here were multiple unknown witnesses at the scene of the alleged incident that did not come forward to provide video evidence they possessed or to give a statement as to what they observed.” The allegation of unlawful force was found “not sustained.”

Interview techniques

Internal Affairs investigators use flawed interview techniques that undermine the quality of investigations. In interrogations of accused officers, investigators exhibit a pattern of failing to ask necessary questions and instead seeking to justify the officers’ actions. This includes asking leading questions that suggest favorable explanations for the officers’ conduct or that minimize the severity of the alleged misconduct. In other instances, investigators failed to press officers on important details or inconsistencies in their statements.

In interrogations of accused officers, investigators exhibit a pattern of failing to ask necessary questions and instead seeking to justify the officers’ actions.

For example, Internal Affairs interviewed an officer who allegedly used excessive force while arresting a woman accused of shoplifting. Throughout the interview, the investigator primarily asked leading questions that fed the officer almost all the relevant details of the encounter. At one point, when the officer had difficulty answering an open-ended question about how much force was used, the interviewer switched back to closed-ended questions that suggested the officer used only limited and appropriate force (e.g., the investigator asked, “A guy of your stature, were you able to just put an arm on her and guide her to your squad car? . . . And there was no more force used than that?” as a way of suggesting that the officer would not have used excessive force given his large frame ((6’ 3”, 295 pounds)). At no point was the accused officer required to provide a narrative account of what happened.

Delays

JPD’s delays in completing administrative investigations undermine the fact-finding process and harm the morale of Department members. Some delays are unavoidable despite the diligence of Internal Affairs investigators, but in other cases, preventable delays may cause necessary evidence to be lost. Investigations that take too long may also undermine the effectiveness of discipline because the sanction is far removed from the underlying incident.

JPD’s policies are not sufficient to ensure timely investigations. JPD policy requires all investigations to be “completed within 60 days of the member being notified of the investigation.” In practice, this means that the 60-day time period begins only once Internal Affairs decides to provide the accused Department member with a Notice of Complaint, which typically happens near the end of an investigation, after all other evidence has been gathered. As a result, months sometimes pass before the Department member is formally notified.

JPD’s policies are not sufficient to ensure timely investigations.

This way of measuring investigation timelines permits significant delays. In one case, nearly six months elapsed from the date the complaint was filed until the accused officer was notified. But because the investigation was concluded within several weeks after that, an investigation that took nearly seven months was considered timely. Though this timeline is not typical of most cases, we identified a number of complaints in which the investigation would be considered timely under JPD policy even though it lasted more than six months.

Even applying the timeliness benchmarks in JPD policy, many investigations took longer than 60 days after the Department member was formally notified of the allegations. And in a significant proportion of those cases, the investigation file does not include a request for an extension, which is required by policy. These cases demonstrate that Internal Affairs is not consistently following the timeliness benchmarks and procedures that currently exist.

Evidentiary and credibility biases

Internal Affairs investigators demonstrate biases in weighing evidence and making credibility determinations. These biases sometimes skew the outcome of investigations, diminishing the integrity of the fact-finding process and the legitimacy of Internal Affairs. JPD does not have written policies about making credibility determinations during administrative investigations, but Internal Affairs personnel informed us that they generally disbelieve statements by community members if they contradict statements by officers, based on a presumption that officers are truthful because they take an oath upon joining the Department.

This credibility bias can result in flawed dispositions. We identified cases in which credibility determinations were central to resolving an allegation and Internal Affairs gave preference to the statements of officers. Even provable, material dishonesty during an investigation is not always sufficient to overcome the presumption of officer truthfulness. In one case, Internal Affairs reached a “not sustained” disposition for an allegation of domestic battery despite evidence that the accused officer’s denial of wrongdoing was not credible. Specifically, JPD investigators determined that the accused officer had falsely reported that the victim was suicidal “in reprisal” for an earlier incident, had sought to use narcotics recovered from their home to gain an advantage in a child custody dispute, and had admitted to multiple criminal investigators that he had “shoved” the victim. Nonetheless, Internal Affairs apparently gave more weight to the officer’s later denials than to the victim’s detailed description of the physical abuse.

Similarly, we identified cases in which Internal Affairs investigators gave greater weight to exonerating evidence, including drawing inferences in favor of accused officers and minimizing objective evidence suggesting misconduct. In one case of alleged domestic violence by an officer, a photograph showed the officer’s girlfriend with two black eyes. In his statement to Internal Affairs, the officer described a physical altercation in which his girlfriend was the aggressor but was unable to explain how she received injuries to her face. Rather than giving weight to the photographic evidence, the investigator asked a leading question suggesting that “something could have happened” to the victim after she left the officer’s house. Apparently crediting its own explanation for the photograph, Internal Affairs found that the allegation of domestic violence was not sustained. (The same officer went on to engage in other acts of domestic violence, harassment, and related misconduct, and he subsequently resigned from the Department).

Credibility bias also affected the outcome of a case in which an officer allegedly struck a high school student in the face while restraining him in the rear of a squad car. Internal Affairs accepted the officer’s statement that he had only used his forearm to push the student back against the seat and did not hit his face. Based on the officer’s denials, the allegations were not sustained. But a witness, a school administrator with no apparent motivation to be dishonest, clearly described seeing the officer deliver a strike with his elbow to the student’s face. Video and audio recordings support the witness’s account. Although video of the backseat is partially obscured by the officer’s body, it shows the officer forcibly swing his arm downward in a manner that is not consistent with simply pushing the student backward. A few seconds later, the front-facing squad camera captured audio of the student’s statement to the officer, “You just hit me in my sh*t,” to which the officer responded, “Good.”

Even provable material dishonesty during an investigation is not always sufficient to overcome the presumption of officer truthfulness.

Flawed dispositions

The above deficiencies in administrative investigations often result in dispositions that are not supported by the evidence. JPD policy establishes four possible dispositions for an allegation:

- sustained - the evidence shows that the Department member violated policy

- not sustained - there was insufficient evidence to find a policy violation

- unfounded - the evidence shows that the allegation of misconduct was false

- exonerated - the evidence shows that the Department member engaged in the alleged conduct but that this conduct conformed to policy and was lawful

JPD policy does not dictate the standard of proof that applies for each disposition. Internal Affairs investigators told us that they apply the “preponderance of evidence” standard (meaning the allegation is more likely true than not), which is appropriate for administrative investigations. But we identified a number of cases in which investigators reached a “not sustained” disposition even where the evidence indicates that it is more likely than not that the Department member engaged in misconduct, suggesting that Internal Affairs applies a more stringent standard of proof in practice.

Internal Affairs fails to properly differentiate between the “unfounded” and “not sustained” dispositions, including in cases that come down to credibility contests between complainants and Department members. In cases where Internal Affairs reached an “unfounded” disposition despite the absence of enough evidence to support that finding, the disposition makes it appear that the allegations were false even when there was simply insufficient evidence to determine what happened.

For example, investigation reports rarely include express credibility findings even when credibility contests are central to resolving the complaint.

One cause of these inconsistent dispositions is the way investigation reports are written. Although these reports are typically detailed and describe all the investigative steps taken, they often fail to adequately explain how the investigator reached each disposition. Investigators often do not make clear what evidence was ultimately considered important or how contradictory evidence was reconciled. For example, investigation reports rarely include express credibility findings even when credibility contests are central to resolving the complaint. Although in some cases the reason for the disposition is obvious in light of the evidence, in others the failure to articulate how the disposition was reached can make the outcome appear arbitrary or biased.

JPD’s disciplinary outcomes are not proportionate in cases of serious misconduct, undermining trust in the accountability system

Disciplinary outcomes are unpredictable and do not reflect a consistent and procedurally just response to serious misconduct. Appropriate discipline necessarily depends on the facts and circumstances of each case, but our interviews of Department members and review of Internal Affairs files demonstrate that discipline is generally lenient, including for serious violations. This contributes to a culture where Department members believe that even serious misconduct will not jeopardize their careers.

Some members of the Department described a culture of light discipline, which was borne out in our review. JPD often failed to impose an appropriately severe disciplinary sanction after Internal Affairs found that a Department member had engaged in serious misconduct. In one case, an officer was found to have engaged in a highly dangerous road rage incident in which he played “cat and mouse” with another driver, culminating in a verbal threat of deadly force by the officer. The officer received only a three-day suspension for willful conduct that endangered his own life and the life of a community member.

JPD issued a similarly brief suspension after it found that an officer, while on duty and in uniform, went to the home of a community member (whom he had met three weeks prior while canvassing the neighborhood for a suspicious vehicle) to make sexual advances. The officer told the woman that he had injured his penis and that his doctor had advised him to treat the injury by having “plenty of sex,” and then he gave her his business card. The officer was required to undergo training on “developing emotional intelligence” and was suspended for just three days: one for using coarse language and two for “conduct unbecoming.”

Some members of the Department described a culture of light discipline, which was borne out in our review.

In another case, an officer was found to have attached an unauthorized extended magazine on his service weapon without the Department’s approval. During a shooting, the officer’s weapon malfunctioned due to the unapproved modification. Despite creating danger for himself and others, he received only a written reprimand.

JPD also imposed lenient discipline against a supervisor who used unlawful deadly force by shooting at a youth driving away in a vehicle. During the incident, the supervisor used poor tactics that exposed officers under his supervision to serious risk, leaving the driver with room to escape and using ineffective communication techniques that escalated the encounter. As the 15-year-old driver attempted to flee, the supervisor fired his gun at the car several times. An investigation conducted by an outside law firm hired by the Department determined that the supervisor violated the Department’s deadly force policy by shooting at a fleeing vehicle that posed no imminent risk. But JPD issued a suspension of just three days—a minor sanction not commensurate with the gravity of the offense and other aggravating circumstances (including the fact that the supervisor failed to acknowledge that his use of deadly force was improper).

These are just a few examples of a much larger pattern of light discipline for serious misconduct. The failure to hold these and other Department members accountable for abuses of authority sends a signal to all Department members that these actions are tolerated. According to one officer we spoke with, Department members know that even serious misconduct, such as domestic violence or using illegal drugs, will not cost them their jobs.

JPD policy states that the Department will use “progressive” discipline, but this term is not defined in any written directives.[20] In practice, JPD’s progressive discipline system has been interpreted narrowly to mean that sanctions will increase only for recurring violations of the same policy, not for repeated instances of misconduct in general. Nonetheless, we identified cases in which the Department failed to impose progressive discipline despite repeated similar policy violations or even told officers that discipline would not be progressive.

Although we determine that JPD’s disciplinary decisions are generally lenient, especially for serious misconduct involving harm to community members, in certain cases JPD imposes discipline that is perceived as harsh or excessive. This leads Department members to believe that the discipline is unfair or arbitrary, and that it may have a political or retaliatory motive. In addition, Department members expressed the view that accountability and discipline are affected by favoritism on the part of JPD command staff. Regardless of whether these perceptions are accurate, they undermine trust in the accountability system. Against the backdrop of a culture of lenient discipline, attempts to impose proportionate discipline may further limit Department members’ willingness to report misconduct and may undermine the legitimacy of Internal Affairs.

Our investigation identified several factors that contribute to inadequate and unpredictable discipline for misconduct, which we discuss below.

Insufficient policies or procedures governing discipline

JPD’s policies lack clear rules or guidelines governing the imposition of discipline. JPD does not use a disciplinary matrix or a similar tool that prescribes ranges of recommended discipline for certain violations. Nor does JPD have a systematic or consistent method for relying on past disciplinary decisions for similar infractions. In the past, Internal Affairs has created lists or tables of comparable past discipline, but it has discontinued that practice.[21] At the same time, the officers’ collective bargaining agreement prohibits the consideration of some disciplinary history if a certain amount of time has passed since the prior discipline.

Although JPD policy lists aggravating and mitigating factors that should be considered when imposing discipline, investigation reports sometimes fail to expressly identify the factors that apply to the incident being investigated. In cases where some of these factors are identified, investigators typically list only the mitigating (and not the aggravating) circumstances. This practice may result in discipline that is too lenient because it fails to account for circumstances that make the misconduct more serious. In addition, documenting all relevant disciplinary factors is necessary to ensure that discipline is consistent and fair.

Reliance on shift-level counseling

As an alternative to discipline, JPD relies heavily on “shift-level counseling,” including in cases involving serious policy violations. In some cases, this involves having supervisors conduct the fact-finding investigation instead of Internal Affairs. In others, Internal Affairs conducts its own investigation and imposes shift-level counseling as a form of corrective action. As a result, shift-level counseling sometimes operates as a parallel system of accountability that removes the case from the oversight of Internal Affairs altogether.

Contrary to JPD policy, which permits shift-level counseling for only “minor . . . allegations of an internal nature, procedural violations, or allegations such as discourtesy, rudeness or poor service,” Internal Affairs refers a broad set of cases to the shift level. These include cases involving allegations of serious misconduct, such as use of force, abuse of authority, and discriminatory policing. In one case, shift-level counseling records show that the officer “used coarse, disrespectful language, telling an arrestee, ‘shut up, don’t you f***ing talk to me,’” and threatening to “slam his head into the car.” Referring misconduct like this for shift-level counseling, rather than imposing appropriate discipline, signals that JPD is unwilling to impose professional consequences on officers who verbally abuse or threaten community members.

Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery

Opportunities to further reduce initial discipline

After the initial disciplinary decision, there are further opportunities for the discipline to be reduced. Not all of these are within JPD's control, but they all lead to the result that Department members rarely face meaningful consequences for their misconduct.

- Compensatory time. Under the officers’ collective bargaining agreement, suspensions can be reduced using compensatory time for up to three workdays. Use of compensatory time undermines the significance of disciplinary sanctions, and it was used in almost every case involving a suspension to reduce or eliminate the consequences of misconduct.

- Administrative review. Department members’ collective bargaining agreements permit members to request an “administrative review” hearing with Department leadership to contest the Chief’s initial recommended discipline. Administrative review hearings often result in lesser discipline, including in cases where the sanction was already relatively lenient. In one case, Internal Affairs sustained allegations that an officer, while off-duty at a bar, showed his badge to several patrons and went through a woman’s purse without her permission so that he could leave his phone number. The initial discipline was two days’ suspension, but after an administrative review hearing, the Chief reduced it to a written reprimand.

- Appeals. Disciplinary appeals make outcomes less predictable. Once a Department member decides to appeal, pursuant to the officers’ collective bargaining agreement, the officer and the Department may meet with the city manager to attempt to resolve the dispute. In the past, this process has allowed the city manager to override disciplinary decisions by the chief.

Officers may also appeal disciplinary decisions either to an arbitrator or to Joliet’s Board of Fire and Police Commissioners. These appeals can significantly reduce discipline. For example, one case involving three officers found to have engaged in serious misconduct against a bar patron[22] resulted in an officer being initially suspended for 18 days.[23] But an arbitrator reduced it to 16 days with 7 held in abeyance—effectively cutting it in half. After applying compensatory time, the officer served only a six-day suspension.[24] - Disciplinary settlements. In many cases, the risk of losing an appeal causes the City to enter into settlement agreements with an accused Department member. We identified a pattern of settlements that significantly reduced discipline for even serious violations, including cases where lengthy suspensions became written reprimands. In a few cases, these agreements recharacterized the alleged misconduct in a way that obscured the fact that the accused officer had been dishonest, which could bar the officer from many assignments. In one case, the City agreed not to release the officer’s disciplinary records or disclose the circumstances of their resignation to prospective employers, such as other police departments.[25] Agreements of this type signal to Department members that serious misconduct, even if it results in termination, will not affect their ability to continue working as police officers.

Settlement agreements are a key way in which the City can override the Department's disciplinary decisions. There appear to be no guidelines or limits on when city officials, including the Joliet city manager, can reduce discipline in the settlement process. In the past, involvement by city officials has resulted in dramatic reductions to officer discipline and created a perception that JPD’s accountability systems are arbitrary or politicized.

* * *

The deficiencies in JPD’s disciplinary system, combined with problems in the earlier stages of the administrative investigation, shield Department members from repercussions for their misconduct. These problems collectively defeat accountability, including for officers who engage in repeated serious misconduct.

To take just one example, one officer was accused in six complaints of serious misconduct over a period of five years. Three of those complaints involved allegations of excessive force, one involved allegations of reckless driving and a threat of deadly force while off duty, and two included allegations of discrimination. One of the excessive-force complaints was classified as informal and administratively closed because the complainant stated he did not wish to proceed with a formal investigation. Another investigation into alleged discrimination (which resulted in a finding of “not sustained”) was marred by a biased interrogation that used leading questions and failed to ask about key details. And although two of the complaints were sustained,[27] after factoring in administrative review, settlements, and compensatory time, the officer ultimately served just three days’ suspension for both cases combined. These cases collectively represent a failure to adequately investigate and discipline misconduct that harms the community and undermines trust in the Department.

JPD personnel responsible for ensuring accountability receive inadequate training and oversight

The deficiencies in JPD’s response to officer misconduct are traceable in part to the Department’s failure to adequately train and oversee personnel responsible for accountability. Internal Affairs investigators do not receive any formal training on conducting administrative investigations or the requirements of JPD’s accountability policies. Although Internal Affairs investigators are generally permitted to seek out and attend trainings through external organizations, the onus is on them to do so. For the most part, training is “on the job.”

JPD leadership also fails to provide adequate oversight of the operations of Internal Affairs.

The absence of formal training contributes to wide variation in how administrative investigations are conducted, including in important areas where JPD policy gives significant discretion to Internal Affairs investigators. These include complaint classification, interview techniques, evidentiary standards for complaint dispositions, and referrals for shift-level counseling. For example, in 2018, Internal Affairs classified just 13% of complaints (8 out of 61) as informal inquiries, which receive the least amount of investigation. In 2021, with different personnel in place, it classified 62% (51 out of 82) as informal inquiries.

JPD leadership also fails to provide adequate oversight of the operations of Internal Affairs. The command-level review is not designed to identify problems in most investigations. Generally, command-level supervisors review only investigations of formal complaints, not informal complaints or inquiries, meaning that Internal Affairs’ handling of these informal investigations—which account for the majority of investigations in recent years—is rarely (if ever) subject to oversight.

The Department does not conduct audits or other systematic reviews of the Internal Affairs unit. As a result, the Department fails to identify investigative deficiencies like the ones identified in this Report. Although the Chief meets occasionally with Internal Affairs personnel to assess the status of pending cases, based on our observations, this meeting mostly involves information sharing from Internal Affairs to the Chief, and it is not used as an opportunity for the Chief to examine the investigative processes of Internal Affairs. Moreover, because these case reviews address only pending cases, they do not cover potential issues with closed investigations. The structure and substance of the case reviews therefore do not serve to identify possible deficiencies in administrative investigations.

JPD’s promotion practices contribute to misconduct

We identified deficiencies in the processes for promoting JPD officers that have resulted in individuals with prior serious disciplinary infractions being selected for supervisory roles. These processes contribute to patterns of misconduct and undermine effective accountability by sending the message that past misconduct is not taken seriously or considered an impediment to securing a promotion.

Promotion decisions are largely made by a separate City entity, the Joliet Board of Fire and Police Commissioners. Illinois law gives the Board primary responsibility for appointing and promoting police officers.[28] Despite their decision-making power, Board members do not receive any specific training about hiring and promotions, and they are not required to possess relevant expertise or experience.[29]

Even though the Department has a limited role in promotions, which consists of making recommendations to the Board, we identified problematic practices that contribute to an overall failure of accountability. The Department considers only the past five years of the candidate’s disciplinary record, even in cases where the candidate was previously disciplined for egregious violations. And in recent years, JPD has recommended for promotion Department members with troubling disciplinary histories, including:

- engaging in inappropriate and degrading conduct toward a subordinate officer, resulting in reassignment, training, and a 10-day suspension

- improperly initiating a vehicle pursuit and then leaving the scene after the suspect crashed without rendering aid or summoning emergency personnel, resulting in a 24-day suspension

- abusive and degrading conduct toward a member of the public,[30] resulting in a 16-day suspension following an arbitration decision

- committing a battery against the boyfriend of a previous romantic partner, resulting in a settlement agreement that imposed a 120-day suspension[31]

Promoting individuals with troubling disciplinary histories signals to rank-and-file officers that problematic conduct is tolerated or even rewarded, and sends a message to members of the community that officers who violate policy or harm community members will not face consequences in their careers.[32]

JPD fails to maintain comprehensive complaint data or analyze its data for patterns of misconduct

JPD does not ensure that all information relating to allegations of misconduct is appropriately documented and maintained in a central location, meaning that JPD cannot access complete information about how those allegations are resolved. And the misconduct data that JPD does maintain is not adequately reviewed or analyzed to identify problems within the department.

Internal Affairs does not consistently learn about complaints against Department members that are received and “resolved” by shift-level supervisors because supervisors who receive a complaint do not always notify Internal Affairs. Instead, supervisors make independent determinations about what allegations to document, and JPD policy leaves wide discretion to supervisors to determine whether Internal Affairs should be notified. If supervisors fail to document complaints or notify Internal Affairs, Internal Affairs cannot discover or investigate those complaints. This has negative effects on the accountability system; for example, if supervisors do not document each shift-level complaint, Internal Affairs cannot assess whether a Department member has engaged in a pattern of behavior that warrants a higher-level investigation or escalating discipline.

During our investigation, we identified problems with JPD’s recordkeeping for shift-level counseling, as records were kept on paper copies in the watch commander’s office rather than within Internal Affairs. We also identified many cases in which Internal Affairs referred cases for shift-level counseling and specified that supervisors were not required to follow up with Internal Affairs in any way. After we requested that JPD provide us its records of shift-level counseling, however, Internal Affairs adjusted its recordkeeping practices. In August 2022, many records of shift-level counseling were uploaded into IAPro alongside the members’ other disciplinary history. In addition, referrals for shift-level counseling after August 2022 typically request that supervisors return completed Notice of Counseling forms back to Internal Affairs, in contrast with past practice. More recently, JPD upgraded its IAPro software to allow all shift-level counseling files to be digitized and centralized in one location. These steps taken during the course of our investigation reflect a significant step toward improved record management.

Internal Affairs does not record the disposition for informal complaints and inquiries in a consistent way, often listing the disposition as “Information Only” even in cases where it finds a policy violation and refers the case for shift-level counseling.

We also have concerns that JPD fails to properly categorize misconduct data. JPD’s classifications of complaints within its IAPro system relies extensively on broad categories such as “conduct unbecoming” and “failure to perform,” which are used for complaints that vary widely in type and severity. In practice, these categories encompass everything from rudeness and traffic violations to racial discrimination and stalking. In addition, IAPro data relating to complaints classified as informal are often limited or inaccurate. For example, Internal Affairs does not record the disposition for informal complaints and inquiries in a consistent way, often listing the disposition as “Information Only” even in cases where it finds a policy violation and refers the case for shift-level counseling. These practices are a barrier to identifying patterns of misconduct and implementing reforms.

* * *

Certain Internal Affairs personnel have conducted high-quality investigations and have demonstrated a willingness to improve their practices. In some cases, their work has identified misconduct and allowed the Department to respond appropriately. Throughout the course of our investigation, various Department members have been receptive to our concerns about accountability processes and have taken steps to address deficiencies. These include revising JPD’s policies relating to complaint intake and improving the centralization of shift-level counseling records. Nonetheless, the Department as a whole has not successfully identified or corrected a number of serious deficiencies in its accountability system. These problems are the result of larger institutional failures, including the absence of sufficient policies, training, and oversight, and span across multiple personnel responsible for ensuring accountability, both past and present. Addressing these systematic problems will require Department leadership to maintain complete and accurate complaint data and to critically examine the sufficiency of JPD’s response to misconduct.