We have reasonable cause to believe that JPD engages in a pattern and practice of discriminatory policing against Black people in violation of the Illinois Civil Rights Act (ICRA) and the Illinois Human Rights Act (IHRA). We are also concerned that JPD’s treatment of Latino people may violate state law. Evidence gathered by our office from community members, JPD members, and other stakeholders, as well as a thorough analysis of JPD’s data and documents, shows that JPD’s policing practices have a disparate impact on Black people and, to a lesser extent, Latino people. The disparate impact of JPD’s enforcement decisions on Black people, even if unintentional, constitutes discrimination in violation of the ICRA and IHRA. Coupled with evidence indicating that some actions by JPD officers are motivated at least in part by discriminatory intent, JPD’s enforcement practices are damaging its relationships with Black and Latino people in the community.

Statistical analyses of JPD’s policing activities show that across a range of enforcement actions—from traffic stops to uses of force—JPD disproportionately uses its enforcement authority against Black people and, to a lesser extent, Latino people.[1] For Black people, the disparities are heightened when the enforcement action is discretionary: JPD officers more frequently arrest Black people compared with White people engaging in the same conduct. Our analysis suggests that this disparate enforcement is at least in part the result of racial bias.

In addition, our investigation found other evidence of intentional discrimination against Black and Latino people. This evidence includes the use of racially derogatory language both toward members of the public and within JPD, as well as JPD’s failure to hold officers and supervisors accountable for racially biased conduct.

The community feels JPD’s bias, and it has degraded the relationship between JPD and the people they serve. Community members told us that JPD treats people of color differently than from White people for the same conduct. They described JPD as biased and prejudiced and in need of diversity and inclusion training. They also reported that they do not trust JPD and do not always feel comfortable calling for help. This strained relationship has the potential to undermine public safety by making the public less willing to cooperate with JPD in responding to crime.

The Illinois Civil Rights Act provides that no local government in Illinois shall “deny a person the benefits of, or subject a person to discrimination under any program or activity on the grounds of that person’s race, color, [or] national origin” or “utilize criteria or methods of administration that have the effect of subjecting individuals to discrimination because of their race, color, [or] national origin.”[2] The Illinois Human Rights Act also prohibits discrimination based on an individual’s actual or perceived race, color, national origin, or ancestry, among other protected categories.[3] Under the IHRA, public officials (including police officers) are prohibited from denying or refusing a person “the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantage, facilities or privileges of the official’s office or services or any property under the official’s care because of unlawful discrimination.”[4]

Under these two laws, it is not necessary to prove an intent to discriminate; the disparate impact alone constitutes discrimination.[5] The disparate effects of JPD’s enforcement practices deprive Black and Latino people of the “equal enjoyment” of the Department's services. The disparity is consistent across several categories of enforcement activities, including traffic stops, searches, arrests, and uses of force.

To investigate the impact of JPD’s enforcement activities on the three main racial or ethnic groups in Joliet (White, Black, and Latino), our office contracted with a research organization at the University of Chicago to conduct a statistical analysis of JPD policing activities. Relying on JPD’s own information and files, we examined several years’ worth of data on traffic stops and post-stop outcomes (traffic citations, vehicle and person searches, and arrests), arrests, and uses of force. We compared racial distributions and patterns of these outcomes to Joliet population benchmarks and to equivalently matched comparison groups. When comparison groups were used, relevant between-person differences other than race were statistically equated across groups. As a result, any differences in outcomes could only be attributable to race and not some other factor (e.g., location, time of day, reported reason for the stop). This statistical matching methodology was used where applicable, mainly for the traffic stop outcomes and uses of force, where groups were matched on such factors as location, time of day, age, and sex, among others. A more detailed explanation of the methodology used can be found in Appendix C.

The results of the analysis establish that Black people are disparately impacted by JPD’s enforcement activities in a manner that violates the IHRA and ICRA. We also found a lesser, though still concerning, disparity in JPD’s treatment of Latino people. Yet, the overall scope and magnitude of these disparities remain unknown because of the limitations of the data, including where JPD fails to collect certain kinds of data, such as on pedestrian stops, and fails to collect race and ethnicity data consistently across all enforcement activities.

Racial disparities exist in JPD traffic stops between White drivers and Black or Hispanic drivers.[6] Importantly, the disparities identified in this section persist regardless of geographic location within Joliet.

Over the five-year period from January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2023, JPD conducted around 38,000 traffic stops. Approximately 35% of these traffic stops were of Black drivers, 32% Hispanic drivers, and 32% White, non-Hispanic drivers. Compared to the population of Joliet as a whole (Joliet is 44.3% White, 33.5% Hispanic or Latino, and 17.1% Black), the distribution of traffic stops by race suggests some amount of bias in how JPD officers enforce traffic laws. This comparison is inexact, however, because the racial makeup of people on the roadways in Joliet at any given time does not necessarily match the racial distribution of the population as a whole.[7] Because of the inherent limitations of comparing population distributions to traffic stop distributions in any municipality, we conducted more nuanced and statistically controlled comparisons of post-stop traffic data to assess the potential impact of disparate policing.

We compared several post-stop outcomes for drivers of different racial groups for JPD traffic stops that occurred between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2023. This analysis controlled for several data points documented by JPD officers, including the recorded basis for the stop as well as the time and place. Controlling for these situational factors ensures that groups being compared are equivalent with respect to observable factors. Any differences in post-stop outcomes can therefore be attributed to race.

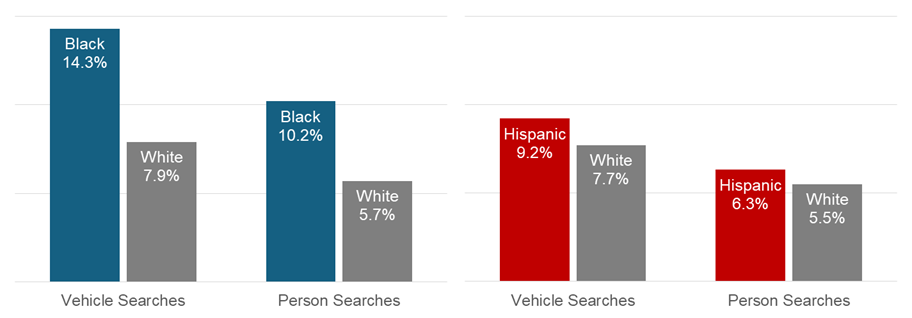

Large disparities emerged with respect to whose vehicle and/or person is searched during a traffic stop. JPD officers are far more likely[8] to search the vehicles of Black drivers (14.3%) compared to similarly situated White drivers (7.9%). These results suggest that between 2019 and 2023, JPD officers searched about 843 more stopped vehicles with Black drivers than they would have if the rates were the same. JPD officers are also more likely to search Black drivers and/or their passengers (10.2%) compared to similarly situated White drivers and/or their passengers (5.7%). This disparity implies that over a five-year period JPD officers searched drivers and/or passengers from about 593 additional stopped vehicles driven by Black drivers.

A similar pattern exists for Hispanic (compared to White) drivers, although to a lesser degree. JPD officers are more likely to search the vehicles of Hispanic drivers (9.2%) compared to similarly situated White drivers (7.7%). These results suggest that JPD officers searched about 182 more stopped vehicles with Hispanic drivers than they would have if the rates were the same. JPD officers are also more likely to search Hispanic drivers and/or their passengers (6.3%) compared to similarly situated White drivers and/or their passengers (5.5%). This disparity implies that over a five-year period JPD officers searched drivers and/or passengers from about 97 additional stopped vehicles with Hispanic drivers than they would have if the rates were the same.

Figure 1: Disparities in Traffic Stop Searches

JPD officers are also more likely to arrest Black drivers (10.5%) compared to similarly situated White drivers (7.1%) during traffic stops. These figures excluded any arrests based on an existing warrant. This means that between 2019 and 2023, JPD officers arrested about 448 more Black drivers during traffic stops than they would have if the rates of post-stop arrests for White drivers and Black drivers were the same.

Controlling for observable factors, JPD officers are substantially more likely to issue two or more citations to Black drivers (29.2%) compared to similarly situated White drivers (21.9%) and are also more likely to issue two or more citations to Hispanic drivers (26.2%) compared to similarly situated White drivers (21.5%). These disparities imply that between 2019 and 2023, JPD officers issued multiple citations to approximately 962 additional Black drivers and 570 additional Hispanic drivers than they would have if the rates were the same.

Sometimes, when a police officer pulls someone over for a minor violation, the officer’s actual goal is to gather evidence of another crime—one for which the officer does not have grounds to detain a driver or even a basis for suspicion. In other words, sometimes officers pull people over for a minor infraction simply to check “whether a person is up to no good.”[9] The practice of dual-motive stops, sometimes called “pretextual stops,” can be constitutional.[10] If the stops are carried out in a discriminatory manner, however, they violate the law.

Reliance on dual-motive stops as a tool to seek evidence of other crimes has serious drawbacks. Studies have shown that dual-motive stops are correlated with racial profiling.[11] Other research shows dual-motive stops have a low yield rate for evidence of other crimes and do not reduce crime overall.[12] More importantly, however, dual-motive stops have a corrosive effect on the relationship between the police and the public, especially communities of color.[13] Recognizing these harmful effects, a number of jurisdictions across the country have recently placed limits on police officers’ authority to make traffic stops for minor violations.[14]

In Joliet, being pulled over is a notably tense situation for non-White drivers. In our review of video footage, we observed the palpable fear of non-White drivers who had been stopped by JPD. We also read reports that illustrated this fear. Some drivers directly told officers that they were afraid or felt threatened. Other drivers waited to pull over (after being signaled by JPD to stop) until they could reach a well-lit area and felt safer. One Black woman was so frightened by her traffic stop encounter that she urinated on herself.

In light of both the general problems associated with dual-motive stops and the specific climate of fear for people of color in Joliet, we analyzed a subset of stops for minor traffic violations—issues like driving without a license plate light or failing to use a turn signal. We examined whether the disparities in post-stop outcomes across traffic stops as a whole were also present in the specific context of minor traffic stops.

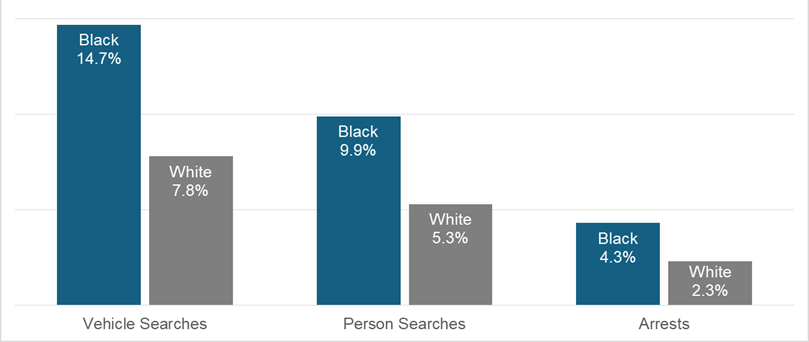

We found that during stops for minor traffic violations, JPD officers are far more likely to search the vehicles of Black drivers (14.7%) compared to similarly situated White drivers (7.8%). These results suggest that, during stops for minor traffic violations over a five-year period, JPD officers searched about 428 more vehicles with Black drivers than they would have if the rates were the same. JPD officers are also far more likely to search Black drivers (and/or their passengers) (9.9%) compared to similarly situated White drivers (and/or their passengers) (5.3%). These results suggest that, during stops for minor traffic violations over a five-year period, JPD officers searched drivers and/or passengers during about 285 more stops involving vehicles with Black drivers that they would have if the rates were the same.

During stops for minor traffic violations, JPD officers are far more likely to arrest (for non-warrant offenses) Black drivers (4.3%) compared to similarly situated White drivers (2.3%), suggesting that over a five-year period JPD arrested about 124 more Black drivers during traffic stops for minor traffic violations than they would have if White drivers and Black drivers were arrested during minor traffic stops at the same rate.

Figure 2: Disparities in Minor Traffic Violations

The disparities we observed regarding minor traffic stops are troubling given the drawbacks discussed above, especially the harmful effect on JPD's relationships with communities of color.

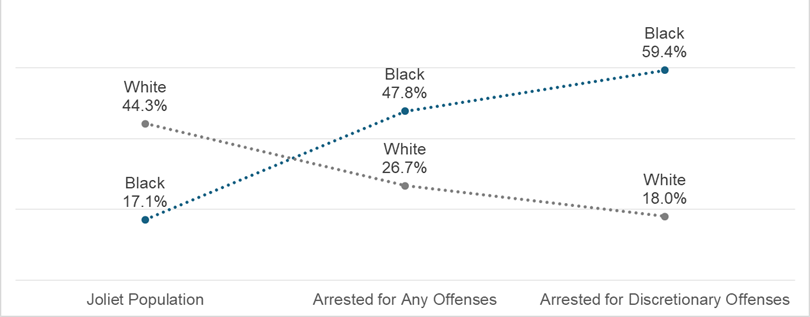

Between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2023, JPD made 25,456 arrests. JPD arrested Black individuals in numbers disproportionate to the size of the Black population of Joliet, and this disparity was heightened where officer discretion was greater.

Black community members are arrested at a rate that is significantly disproportionate to the size of the Black population in Joliet. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that Black people make up 17.1% of the Joliet population. However, between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2023, 47.8% of people arrested by JPD were Black. This disparity was especially pronounced for Black men, who accounted for 37.0% of the arrests despite representing less than 10% of Joliet’s population.

This difference in the proportion of arrests between Black people and White people compared to the population has many possible explanations, including racial differences in exposure to law enforcement (e.g., where police are deployed), racial differences in rates of committing offenses, and the likelihood that at least some people arrested in Joliet are not Joliet residents (and thus not counted in the census).[15] Therefore, while the disproportion found here is large and suggestive, we examined this disparity further by analyzing arrests for discretionary offenses.

Our review of discretionary arrests corroborates our finding of racial disparity. A “discretionary” offense is one for which an officer must use a greater degree of judgment to determine whether the offense has occurred. With many offenses, the violation of the law is fairly clear cut—for example, if an officer knows that a person has taken something from a store without paying, the officer does not need to exercise much judgment to conclude that the person may have committed retail theft. But other offenses are more likely to require an officer to subjectively evaluate the facts to determine whether there is probable cause to make an arrest. Discretionary offenses include such charges as disorderly conduct[16] and resisting or obstructing a peace officer (a charge that may include resisting arrest).[17] Usually, disorderly conduct and resisting or obstructing charges are paired with other more substantive charges, but occasionally these are the only charges of record. Arrests involving only charges in which officers have more discretion provide a greater opportunity to observe any bias that may be at play.[18]

For the 577 arrests that occurred between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2023 where either disorderly conduct or resisting or obstructing of a peace officer was the only charge, Black individuals comprised 59.4% of those arrests and White individuals comprised 18.0% of those arrests. In other words, Black individuals were more than 2.5 times more likely than White individuals to be arrested on a disorderly conduct or resisting or obstructing charge alone, without a more substantive charge. Moreover, the rate of arrests of Black people for discretionary offenses is about 20% greater than the rate of arrests of Black people overall in the same time period (59.4% vs. 47.8%). Thus, even if factors other than bias could explain the overall difference in arrest rates between Black people and White people, the heightened disparity for discretionary arrests (which involve more subjectivity and judgment on the part of officers) is evidence of bias.

Figure 3: Proportion of Black People in Joliet, Arrested for Any Offenses, and Arrested for Discretionary Offenses

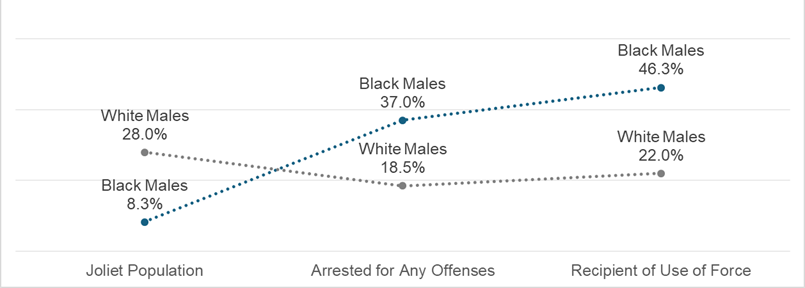

Black community members, especially Black males, are subjected to force by JPD at a rate that is significantly disproportionate to the size of the Black population in Joliet. Although Black males make up less than 10% of the population, they accounted for 46.3% of the 1,258 uses of force that JPD recorded between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2023. The rate of force used on Black males (46.3%) is substantially higher than the arrest rate for Black individuals (37.0%) in the same time period, suggesting that the disparity in force used between Black and White individuals is not strictly a result of the disparity in who is arrested. Rather, the additional disparity in the use of force against Black males (over and above the disparity in arrets rates) appears to be attributable to some other factor(s).

The disparity in uses of force against Black males is consistent across all levels of force, including soft tactics (e.g., joint locks, pressure points), hard tactics (e.g., hand strikes, take downs), and use of weapons (e.g., expandable batons, tasers, firearms). In fact, the disparity is more pronounced when officers use weapons—Black males represent 49% of such uses of force. It is also noteworthy that of the instances of unlawful force we identified in our investigation, half were against Black males.[19]

JPD itself has recognized the disproportion in its use of force against Black males. JPD’s 2023 annual Use of Force Review Report noted that for the years 2019 through 2023, Black males have represented an average of 50% of all individuals who are subject to force by JPD. JPD did not identify a valid law enforcement explanation for this finding.

When we restricted our sample to only those uses of force in which the most serious charge was disorderly conduct or resisting or obstructing a peace officer (i.e., discretionary offenses where bias is more likely to play a role), Black individuals (6.3%) were subjected to hand strikes or punches at a far higher rate than similarly situated White individuals (2.0%) where groups are matched on the time of day, reason for force used, age, sex, build of the individual, and race of the involved officer.

Figure 4: Proportion of Black Males in Joliet, Arrested for Any Offense and Recipient of Use of Force

JPD has maintained a gang database for at least 25 years. According to JPD, the purpose of its database is to identify gang members for investigative purposes and other uses, like seeking to move cases from juvenile to adult court or to enhance criminal sentences. JPD’s Intelligence Unit enters individuals into the database based on information developed through criminal investigations and social media surveillance.

Gang databases are governed primarily by federal regulations, which require police departments that receive federal funds and operate gang databases—both of which JPD does—to ensure that its systems are fair, accurate, and up to date.[20] They prohibit departments from collecting and maintaining information unless there is reasonable suspicion that the individual is involved in criminal conduct or activity and the information collected is relevant to the criminal conduct or activity.[21] Under the regulations, there is reasonable suspicion to include someone in a gang database when there is “a basis to believe that there is a reasonable possibility that an individual or organization is involved in a definable criminal activity or enterprise.”[22] Further, the regulations mandate that departments purge all database information if it is no longer relevant or reliable.[23] In any event, departments must purge information from the database after five years, unless the periodic review reveals continuing reasonable suspicion that the individual is involved in a definable criminal activity or enterprise.[24]

We identified racial disparities in JPD’s gang database. At the time of our review, JPD’s gang database contained 1,244 entries. Of those entries, 73% were identified as Black, 17% were labeled as Hispanic, and 10% were labeled as White. Moreover, about half of the individuals identified as White were associated with predominantly non-White gangs. JPD acknowledged during our investigation that there are other criminal organizations that may fit JPD’s (or the State’s)[25] definition of a gang but that are not the focus of JPD’s intelligence gathering efforts. White nationalist groups are an example. According to JPD, the database previously tracked one member of a White nationalist organization, but he has been purged from the database for lack of contacts. JPD admitted that it has focused on “street gangs” that use names or monikers, common signs, and signals, even though the definition of “gang” under Illinois law is much broader. JPD also acknowledged that motorcycle gangs with primarily White memberships are active in Joliet, but their members do not end up in the database because JPD’s inclusion system relies on police contacts. But this reasoning is circular—if JPD focuses on Black and Latino gangs, it will have more police contacts with members of those groups and therefore more information to include in its database. JPD’s choice to focus on gangs associated with Black and Latino people, even though White gangs are also present, is evidence of bias.

JPD’s gang database policies and practices do not provide an appropriate level of guidance to officers and supervisors, nor are they consistent with the federal regulations. In particular, JPD’s gang database policies and practices suffer from the following deficiencies:

- JPD’s gang database policies are outdated, vague, and lack critical definitions of key terms, such as “gang,” “street gang,” and “motorcycle gang”[26]

- JPD’s database inclusion checklist and point system are overbroad and are not sufficiently tied to criminal activity, placing undue emphasis on factors like tattoos and being in the company of self-identified gang members[27]

- JPD’s gang database recordkeeping is inconsistent and unreliable, particularly as it relates to the failure to digitally track the reasons for which individuals were included in the database

- JPD does not regularly audit the information in the gang database or appropriately track the information it disseminates to other entities, contrary to federal regulations[28]

- JPD’s system for purging individuals from the database is ineffective. Individuals are kept in the database beyond the five-year maximum for non-criminal conduct, such as consensual contact and traffic stops. In addition, JPD maintains an archive database with historical information, including a list of individuals JPD has allegedly purge

These policy and practice deficiencies have resulted in a system that creates an unreasonable risk of discrimination.

Gang databases can contribute to criminalization, stigma, and other consequences.[29] And JPD in fact uses its gang database for sentencing, jail assignments, and extra-jurisdictional investigations. The potential consequences of being named in the database can be life changing and highlight the critical need for JPD to carefully adhere to procedural safeguards contemplated in the federal regulations. This is underscored by the likelihood that the database includes individuals who are not engaged in true gang-related criminal activity.

* * *

Our analysis of JPD’s enforcement activities shows a pattern in which JPD uses its enforcement authority more often and more heavily against Black people (and, to a lesser degree, Latino people) than against White people. The pattern is widespread, both across enforcement categories and across the city. This disparate impact constitutes discrimination under the ICRA and IHRA.

A window on St. Mary Carmelite Church

Black and Latino communities in Joliet feel racial animus from JPD. The investigative team spoke to Black and Latino individuals who reported their perception that JPD fails to take their concerns as seriously as those of White people. In multiple conversations, community members expressed that JPD fails to appropriately investigate the deaths of Black people, writing them off as drug- or gang-related. Families do not feel they are heard or cared for by officers, reinforcing strongly held beliefs that JPD is not there to serve and protect all people in the Joliet community.

Black and Latino people report feeling harassed by JPD. They expressed the view that JPD targets individuals just for existing in Black and Latino neighborhoods. Officers reportedly tell community members they can frisk anyone if they are in a known “drug neighborhood.” This is clearly at odds with the law,[30] but is consistent with the views of a JPD officer who spoke of “thugs doing thug sh*t in thug places.” Other community members reported to us their belief that JPD officers use a person’s race or ability to speak English fluently as a precondition for how they will treat that person. Community members also shared that they believe that JPD officers target young men of color in cars, often using minor traffic infractions and difficult-to-disprove claims (such as the smell of marijuana) to justify searches.

The community’s perceptions are not surprising: our investigation uncovered evidence showing that JPD’s policing practices not only have a disparate impact on Black and Latino people, they are also motivated in part by discriminatory intent.

Discriminatory intent is demonstrated by “such circumstantial and direct evidence of intent as may be available.”[31] Circumstantial evidence of discriminatory intent includes “[t]he impact of the official action [and] whether it bears more heavily on one race than another,” departures from an agency’s normal procedures and accepted practices in the field, and the use of racial slurs.[32]

Here, evidence of discriminatory intent comes from multiple sources. First, the magnitude, pervasiveness, and consistency with which JPD’s policing bears more heavily on non-White people, especially Black people, strongly supports an inference that racial animus is a motivating factor. Second, some JPD officers use racial epithets and racially coded language in their interactions with members of the public, with little consequence. Third, these public expressions of bias are echoed inside of JPD, even by and in the presence of supervisors. Fourth, JPD does not adequately respond to complaints of racial bias and does not hold officers accountable.

The data presented above shows that JPD’s actions have a disparate impact on Black and Latino people. Disparate impact alone is usually not “determinative” of discriminatory intent, but it is “an important starting point.”[33] In this case, the disparate impact of JPD’s enforcement activities is so pervasive and so consistent, and, in some cases involving Black people, so dramatic that the only reasonable inference is that it is motivated at least in part by an unlawful discriminatory purpose.

When Black and Hispanic drivers are pulled over, they and their passengers are more likely to be subjected to a search of the vehicle or their persons than similarly situated White drivers and their passengers. They are also more likely than White drivers to be given two or more citations when pulled over for the same initial infraction. Black drivers are also more likely to be arrested after being pulled over than similarly situated White drivers. This disparity holds even when controlling for location, so the difference is not attributable to traffic stops of Black drivers occurring in higher crime areas. Black people are also arrested generally at a higher rate than White people and are more likely to have force used against them, at rates even greater than the disparity in arrests. JPD’s gang database also overwhelmingly tracks Black and Latino men, despite the presence of White gangs in Joliet.

The consistency of this disparate enforcement against Black and, to a lesser extent, Latino people, across so many different enforcement activities (and often in circumstances closely mirroring those in which White people are subjected to less enforcement activity) suggests that the disparity is not part of any legitimate strategy for combatting crime but is instead the result of bias based on race, color, and/or national origin.

JPD officers also make discretionary arrests of Black people for resisting/obstructing at rates that far exceed the rates of such arrests for White people and which greatly exceed the disparity in other, less discretionary types of arrests. And when a discretionary offense (disorderly conduct, resisting arrest, obstructing a peace officer) is the most serious charge in an arrest, Black people are more likely to have force used against them. We have failed to identify any valid law enforcement justification for JPD’s pattern of exercising its discretion to disproportionately arrest Black people and use force to in effectuating those arrests.

Finally, some aspects of JPD’s pattern of disparate enforcement are simply so “stark” and “clear” that they are “unexplainable on grounds other than race.”[34] JPD’s disproportionate use of force on Black males—at rates at least five times higher than their numbers in the population and significantly higher than the rates at which they are arrested—cannot be explained except as partly a product of racial bias. That is to say that while some of the disproportion is likely due to other factors, such as the disparate exposure to law enforcement and the presence in Joliet of people who are not residents, it is not plausible that all the disproportion can be accounted for by these non-discriminatory factors—the disparity is just too large. The disparity in arrests for resisting or obstructing between Black people and White people is similarly dramatic. It is reasonable to infer that race is a “motivating factor” behind these disparities.

Certain JPD officers’ use of racial slurs and racially coded language in the community, with little or no consequence, is also evidence of JPD’s discriminatory intent. Community members shared that JPD officers have used the term “n****r” either referring to them directly or to others. On multiple occasions, we were told of a 2021 incident in which, in response to an altercation among several Black people, an officer was heard to say “let’s watch those monkeys kill themselves.” This comment was made in the presence of at least one JPD supervisor, and at least one community member reported it directly to the Chief. Community members have also told us that JPD officers use their social media to spread derogatory and racist information. At a city council meeting, one person shared that a JPD officer posted things like “you can take the rat out of the hood but you can’t take the hood out of the rat.”

Our investigation affirmed these community members’ experiences. In 2017, a Black man pulled his car to the side of the road due to engine trouble. A JPD officer pulled over, exited his squad car, pointed a gun at the driver and yelled “Freeze! Don’t move n****r or I’m going to kill you!” The driver’s White companion was in the car and heard the exchange. The driver was later released with no charges. JPD settled a lawsuit the driver filed for $3,500, but JPD never investigated the incident or disciplined any officer. In 2019, JPD received an anonymous complaint stating that an officer had asked a Black driver how he “acquired such a nice truck being a n****r,” and that the officer changed his demeanor only when he realized the driver was military. The complainant later called JPD Internal Affairs and gave more detailed information, including pinpointing the time and location of the traffic stop, but also stated that they wanted to remain anonymous. Without taking any further action, Internal Affairs “administratively closed” the case, a disposition used to indicate that Internal Affairs either could not complete the investigation or could not determine a disposition.

Further, in April 2022 an officer posted a racist meme on his personal Facebook page (under a pseudonym but with his face visible in the profile picture). The meme was titled “Breaking News” and had a caption that read:

Sad News From Disney! This is so disappointing. CNN reported today that Walt Disney’s new film called “Jet Black,” the African-American version of “Snow White” has been canceled. All of the 7 dwarfs: Dealer, Stealer, Mugger, Forger, Drive By, Homeboy, and Shank have refused to sing “Hi Ho, Hi Ho” because they say it offends black prostitutes. They also say there ain’t no way in hell they’re gonna sing “It’s off to work we go.”

A second JPD officer commented on the post, writing only “bruh” (an ambiguous response), and a JPD dispatcher liked the post. Command staff instructed Internal Affairs to refer the matter to the officer’s supervisor for shift-level counseling. The supervisor then “counseled” the officer by providing him with a copy of the social media policy and directing him to delete the post.

These public displays of bias and hostility based on race, color, and/or national origin do incalculable damage to JPD’s relationship with the community, especially when officers act this way with impunity. They also lend support to the conclusion that JPD polices in a biased way.

Officers reported to our investigative team that it is not uncommon to hear JPD members use racial slurs, including the n-word, while on duty. One officer reported that he overheard an on-duty lieutenant say “stupid f***ing n***r” while in the presence of another JPD supervisor. In another incident, an officer reportedly said to another officer, “I don’t know how you interact with these animals” referring to individuals in Latino neighborhoods.[35] In 2022, an officer told a dispatcher that she had a black cat she nicknamed the “house n***a.” Unlike in other instances, this incident was actually reported, and Internal Affairs sustained the allegations against the officer. However, the incident raises the question of why a JPD officer would feel free to use such language in the first place.

In some instances, the biased conduct is less explicit, though no less troubling. For example, Black officers have faced disparagement for their appearance. In one incident, a Black officer came to the station wearing grey sweats and black Air Jordans. A White officer said “Oh, you’re wearing a uniform today”—meaning the attire of a black criminal. We have heard reports that when officers need to request a collar for a dog, they will request a “noose”—a word that has obvious racial connotations. Black officers have also faced scrutiny for their hairstyles. In an incident involving a newly hired officer who wore his hair in braids, a deputy chief instructed the officer’s field training supervisor to tell the officer to change his hair style, even though his hair was within the requirements of JPD policy.[36]

White officers also reportedly discourage recruits from joining the Black Police Officers’ Association (BPOA), a professional organization that, among other things, advocates for the interests of Black officers at JPD. One officer complained to Internal Affairs that a sergeant told him fellow officers distrusted him (the officer) because he was a member of BPOA. Another officer told us that being in the BPOA puts a target on an officer’s back in the view of fellow officers.

Our investigation indicates that bias against people of color is common at JPD. Even if it is not always directed at members of the public, the hostility that non-White officers experience within JPD, especially at the hands of JPD supervisors, is additional evidence that JPD’s disparate policing practices are motivated by discriminatory intent.

JPD’s responses to and investigation of allegations of discrimination are inadequate to provide accountability for the community members’ complaints. First, JPD mischaracterizes complaints involving bias, masking their racial content. Second, JPD does not adequately investigate allegations of racial bias and does not sustain allegations when warranted.

When faced with complaints of profiling or other forms of racial bias, JPD’s Internal Affairs investigators too often summarize or paraphrase the complaints in their final reports in a way that hides any race-based allegations. For example, in 2018, a Black woman complained about a traffic stop involving her Black son. On the complaint form, she checked the box for discrimination and wrote in “profiling” in the section asking for allegations (she also provided additional information about the incident). In the final investigatory report, the allegations (which were not sustained) were stated as “conduct unbecoming” and “improper arrest”—phrases that do not reflect the racial content of the initial complaint. A complaint from 2021 included allegations of false arrest and a statement that officers were being racist. Despite this, the investigation report summarizes the complaint as only being concerned with false arrest, and the only formal allegation (which was deemed unfounded) was “False arrest.” Even when allegations are sustained, the formal allegations do not reflect the race-based content of the incident being investigated. In the 2022 incident discussed above, in which an officer told a dispatcher that she had a black cat she had nicknamed the “house n***a,” Internal Affairs sustained allegations of “conduct unbecoming,” “coarse or disrespectful language,” and “harassment in the workplace.”

In addition to signaling that JPD does not prioritize confronting discrimination based on race, color, or national origin, mischaracterizing complaint allegations has concrete consequences. First, it means that complaints of misconduct against an officer will not be recorded as involving racial bias. This will make it harder for JPD leadership to detect patterns of biased policing by a given officer, as well as identify patterns across the Department as a whole that could require additional training or other actions.

Second, this mischaracterization has the potential to affect the constitutional rights of criminal defendants. According to the Will County State’s Attorney’s Office, police in all departments in the county are expected to inform the State’s Attorney of any sustained findings of racial bias. In some circumstances, the State’s Attorney is obligated to turn this information over to defense attorneys.[37] When JPD fails to acknowledge and document the racial character of allegations, even a sustained allegation will not result in a finding of bias. This practice could cause the finding to go unreported to prosecutors, as well as undisclosed to a criminal defendant, potentially violating their right to a fair trial.

JPD also fails to adequately investigate allegations of racial bias and fails to sustain allegations when clear evidence of bias exists.

In addition to mischaracterizing allegations of racial discrimination, investigators also often ignore these allegations when investigating complaints of misconduct. In one example, a Black woman complained about JPD’s treatment of her at a traffic stop. During the investigator’s interview with the woman, she made three different statements clearly indicating that she believed the treatment she received was due to her race: she stated that she thought the officer needed diversity training, that the officer “could be just an a**hole [or] he could be racist, he could be both,” and that the officer “got a good look at who was driving [i.e., a Black woman]” before he pulled her over. Despite these clear references to race, the investigator did not ask a single question about the subject. In fact, during the interview with the woman, he summarized her complaint as involving “coarse and disrespectful language.” The investigation report shows that the investigator met with the woman’s attorney, who stated that the woman was afraid of officers because she was Black. Yet in three interviews with officers involved in the incident, the investigator did not ask whether race was a factor in the stop or in their treatment of the woman, nor did the investigator take any other steps to investigate whether race was involved. The allegations of “conduct unbecoming of a department member, using coarse or disrespectful language, and fail[ure] to explain reason for the traffic stop” were not sustained.

Old Route 66 sign

Investigators should look at additional information such as an officer’s traffic stop history, charging history, or previous complaints to see whether there is reason to be concerned that bias or discrimination might be an issue.[38] In our review of Internal Affairs cases from 2018 through 2022, we identified only one case in which JPD investigators looked at this type of information. That case, which occurred in 2022 after this investigation began, may signal a change in JPD’s practices toward more thorough review of claims of discrimination. If so, it is an important step.[39]

JPD also fails to sustain allegations of bias even when biased conduct unequivocally occurred. In a 2017 incident, a driver accused an officer of pulling him over because he was Black. The officer denied that race motivated the traffic stop, but he admitted to an Internal Affairs investigator that he told the driver that he, a White officer, had “dated better looking Black women” than the Black driver had. This comment—which is both racist and sexist—resulted in no consequences at all for the officer, as the allegation of disrespectful language (an inadequate characterization of the conduct) was not sustained.

In the 2022 incident discussed above in which an officer posted a racist meme to his personal Facebook page, the officer admitted to posting the meme, a clear violation of JPD’s social media policy at the time. But this admission did not result in a sustained finding. Instead, JPD leadership (command staff including the chief) decided to handle the matter through shift-level counseling (which, while technically considered discipline, in this case consisted of nothing more than a review of the social media policy). The complaint was classified as informal, and the investigation was halted. In addition to not imposing meaningful discipline on the officer who posted the meme, JPD failed to initiate internal complaints against the dispatcher who had “liked” the meme or the officer who had posted an ambiguous comment, either for their own conduct or for their possible failure to report the misconduct (there is no record that either reported the post to JPD as they were required to do under JPD policy).

* * *

JPD’s enforcement actions—including traffic stops, searches, arrests, and uses of force—have a disparate impact on Black and Latino people. Based on evidence gathered in our investigation, this disparate impact is at least in part the result of bias toward Black and, to a lesser extent, Latino people. Racially biased policing has eroded community trust in Joliet, and it may also be undermining JPD’s ability to solve crime. Community distrust of police creates a barrier to information gathering during criminal investigations. For example, where there is a lack of trust between the community and police, police will receive fewer tips related to offenses.[40] JPD must address the bias in its operations, both to comply with the law and to fulfill its responsibility to all members of the Joliet community.